1 Management Development Institute, Gurgaon, Haryana, India

2 National Productivity Council, Delhi, India

3 Institute of Management, NIRMA University, Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India

Creative Commons Non Commercial CC BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License (http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-Commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed.

The literature on equity sensitivity is fragmented and has numerous inconsistencies, with various conjoined fields being studied. Given the shortcomings that equity sensitivity fulfils in the workplace equity theory and the predictive power of the construct to explain the workplace attitudes and behaviours, this review aims to synthesise the highly fragmented studies, highlight the publication activity, propose a framework based on a content analysis and identify the research gaps in the area of equity sensitivity. This review also aims at suggesting future research avenues in the field of equity sensitivity. Using a systematic literature review approach, the present study reviews 74 articles published from 1987 to 2020 on equity sensitivity. The review provides a content analysis-based framework for future directions of research and reveals a lack of consensus around a theoretical framework and ambiguity in the conceptualisation of the equity sensitivity. Additionally, the lack of longitudinal qualitative research with limited sample selection are the methodological gaps hindering the field’s progress. This work will help future researchers, interested in extending their contribution to this field.

Equity sensitivity, systematic literature review, benevolent, entitled, workplace justice, organizational behavior

Introduction

The theory of equity (Adams, 1963; Walster et al., 1973; Weick, 1966) has gained a lot of attention from researchers in psychology and human relations. The theory is based on Festinger’s theory of cognitive dissonance and postulates that an individual psychologically compares his/her job inputs and outcomes with their referent others (Adams, 1963). However, the equity theory has primarily been criticised on the grounds of homogenising individual response to the equity/inequity conditions thus ignoring the individual differences in shaping these responses. To overcome this shortcoming, Huseman et al. (1985, 1987) introduced the concept of ‘equity sensitivity’.

Equity sensitivity categorises individuals into benevolent (individuals more inclined towards inputs rather than the output), equity sensitive (who like to maintain a balance between their level of inputs and the outcome they receive) and entitled (individuals who are focused on obtaining more output for the input they provide). These individuals react to equity/inequity conditions differently depending on demographic and psychological variables. Equity sensitivity is believed to enhance the equity theory’s predictive power (King Jr et al., 1993). Equity sensitivity’s superiority is proposed due to the following reasons. First, the equity sensitivity of an individual aids in establishing behavioural clarity in ambiguous workplace contexts (Otaye-Ebede et al., 2016). Second, equity sensitivity offers a holistic apprehension of the equity process by incorporating the individual difference variable (King Jr et al., 1993). Third, Mudrack et al. (1999) highlight the importance of equity sensitivity in explaining the behaviour of individuals in an ethical dilemma situation in the workplace which augments its applications further.

Given the shortcomings that equity sensitivity fulfils in the workplace equity theory and the predictive power of the construct to explain the workplace attitudes and behaviour, a systematic literature review (SLR) was carried out to study the domain. The past literature has been confounding in terms of determining the nature of the domain (Huseman et al., 1987; Miller, 2009), conceptual underpinnings (Huseman et al., 1987; King Jr et al., 1993; Sauley & Bedeian, 2000) of the concept and its dimensionality (Davison & Bing, 2008; Huseman et al., 1985; Sauley & Bedeian, 2000). In response to this increased fragmentation of the findings and aforementioned inconsistencies prevalent in the literature, this SLR aims to provide an integrated view of the research, categorising and identifying the problems in the existing literature and proposing new avenues for future research. This review will serve as a relevant push for the future researchers to investigate the role of equity sensitivity in predicting the various outcomes by developing perceptions in a workplace.

To achieve these objectives, this research is guided by the following research questions:

Recent years have seen a decline in the equity sensitivity research possibly due to the underdeveloped foundation of the concept. Thus, the authors propose a conceptual model of equity sensitivity, which will help broaden the understanding of the role of equity sensitivity as an individual difference variable in the workplace setting. Thus, the review is organised as follows: first, equity sensitivity is introduced, followed by the research methodology. Second, the description of the literature is provided along with an overview of the selected articles. Finally, the findings are highlighted, and future research avenues are suggested.

Methodology

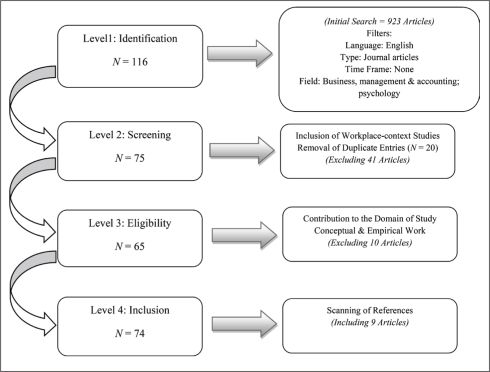

Literature reviews are believed to lay the groundwork to advance a concept or theory and help in tracing the evolution of a phenomenon over time (Kumar, 2022; Kumar et al., 2023a). Therefore, the methodology for reviewing the literature must be systematic, scientific, comprehensive and explicitly report all the steps and procedure for conducting the review (Tuli et al., 2023c). Following Tranfield et al. (2003), the study has used SLR methodology to review the existing literature on equity sensitivity. The review process adopted to summarise the existing research and to identify the future research agenda has been categorised into 4 phases, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Summary of the Systematic Review Process.

To keep the review comprehensible, the study focuses on the literature of equity sensitivity and excludes the job equity theory, although closely related to the interest. This is due to two reasons: First, multiple reviews have been conducted on job equity (Carrell & Dittrich, 1978; Pritchard, 1969), whereas no such review has been done for equity sensitivity. Second, equity sensitivity categorises individuals, which facilitates the understanding of the behavioural and psychological effects of perceived equity/inequity (Huseman et al., 1985, 1987). Thus, a prolific amount of literature is out of the scope of the research area. To uphold the quality of the research, the authors have only included peer-reviewed scholarly articles published in academic journals, which ensure a high-grade inclusion.

Literature Collection and Boundary Identification

The PRISMA model was used to carry out the search to enhance the rigor and objectivity of the search procedure (Moher et al., 2009; Tuli et al., 2023a). The steps are discussed in detail below.

Step 1: Identification

Literature for this review has been identified with the help of keyword/phrase search. Subsequently, the authors delimited the selected literature using a combination of deductive and inductive approaches. As input criteria initially, the use of keywords like ‘workplace equity’ or ‘equity sensitivity’ or ‘sensitivity model’ or ‘inequity’ was made. Several research databases have been used to ensure the inclusion is comprehensive and includes a diverse range of articles in the review. Emerald, ProQuest, EBSCO, JSTOR, SAGE and Elsevier have been used to search the articles. The first round of the database search was confined to keywords, title and abstract. This resulted in 923 articles depicted in Table 1. Additional delimiting boundaries for screening the literature were developed. These boundaries were given as:

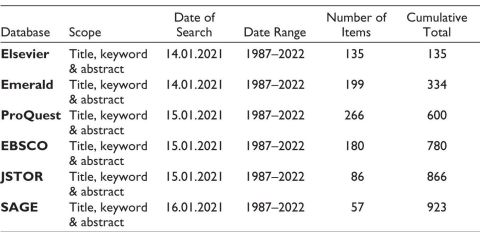

Table 1. Details of Article Search in Database.

\

This led to a total of 116 articles.

Step 2: Screening

To make the study impactful, abstracts were filtered to include the studies conducted in the workplace context. Additionally, 20 articles duplicated in more than one database were removed. Subsequently, 41 articles were excluded from the final sample which led to the inclusion of 75 articles for the final review.

Step 3: Eligibility

The full texts were then obtained for the articles. These articles were analysed for their contribution towards the application or refinement of the domain, development of a scale to measure the domain as well as building theories to enhance the knowledge of the concept. Consequently, only conceptual and empirical papers were included. Any review articles directly addressing the domain were decided to be excluded but apparently no such study was found. This led to the inclusion of 65 articles in the review.

Step 4: Inclusion

Further, to make the data set comprehensive and to include all the relevant articles, detailed scanning of references of all selected articles were done. Finally, 9 articles were included in the final sample, which took the final selection to 74. A proper worksheet was maintained to record the summary of the final included articles, which were reviewed to record various parameters including:

The synthesis of the literature review involves itemisation of selected articles, and it unearths the explicit and implicit relevant facts from the existing body of knowledge. A detailed process of article selection is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Article Selection Process.

Description of the Literature

This section provides a description of the existing literature in the equity sensitivity domain that will help provide insights into the current developments in the domain (Kumar et al., 2023a).

Publication Activity

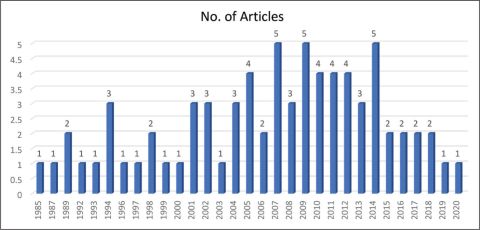

As evident by Figure 3, the equity sensitivity research has been following an increasing trend from 3 articles before 1990 to 10 during the 1990–1999 period and eventually to 59 articles distributed over the 2000–2022 span.

Figure 3. Year-Wise Publication.

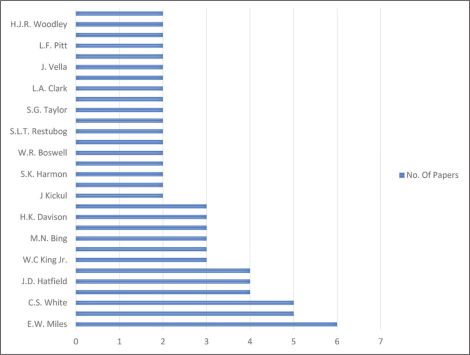

The 74 articles included in the review are published in 43 different journals, constituting fields such as psychology, management, ethics and behavioural sciences and marketing. A total of 32 journals (74%) of the 43, have published only single article and only four journals have published four or more articles. Figure 4 shows the journals with more than one publication in the field. Figure 5 depicts the authors who have contributed significantly to the field.

Figure 4. Journal-Wise Publication.

Research Approaches and Methods

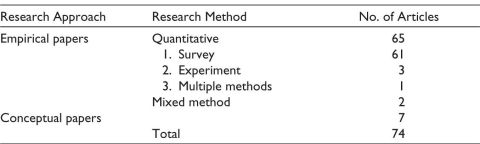

The majority of the reviewed articles were empirical (n = 67), with a mere seven articles opting for a conceptual study. Table 2 depicts the different methodologies adopted by the studies included in the review. Surveys were observed to constitute a large number of studies followed by the conceptual method. Among the articles included in the review, no literature reviews were found, which strengthens the fact that equity sensitivity literature is still underdeveloped.

Table 2. Research Approaches and Methods Used in the Articles.

Nature and Geographical Distribution of the Studies

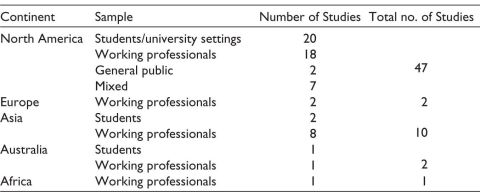

Table 3 depicts the geographic distribution as well as the nature of the sample employed in the empirical articles reviewed. The majority of the articles were based on the sample from United States (44 studies) followed by Canada (3 studies) and Korea, Australia and the Philippines (2 studies each). The analysis also indicated five articles conducted in a cross-country setting and seven studies employing a mixed sample.

Figure 5. Author-Wise Publications.

Table 3. Nature and Geographic Distribution of the Sample.

Three of the studies explored the impact of equity sensitivity under team setting. Political ideology/setting, gender influence, generation gap and negative effects of equity sensitivity found their place in two studies each. Additionally, all the articles included in the review used the cross-sectional method of data collection as no longitudinal study was found.

Findings

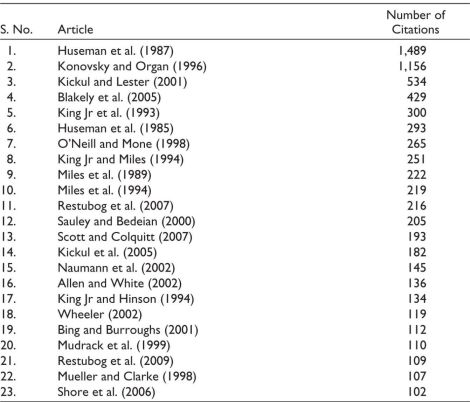

Citation Analysis

Citation analysis refers to the analysis of the number of times an article has been referred to in other studies to identify the most influential works in the field. This will also help in identifying the articles that are most impactful in deepening the knowledge of the field. For this purpose, the citation information provided by Google Scholar as of March 26, 2022 was used. The 74 articles were found to have 8,829 citations making the average citation as 119 per article. The articles with more than 100 citations are shown in Table 4. It was found that Huseman et al. (1987) is the most-cited article with 1,489 citations. This might be due to it being a seminal study. Other top-cited articles were Konovsky and Organ (1996), Kickul and Lester (2001) and Blakely et al. (2005).

Table 4. Citations of the Reviewed Articles.

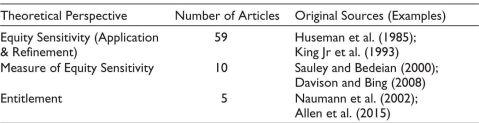

Content Analysis

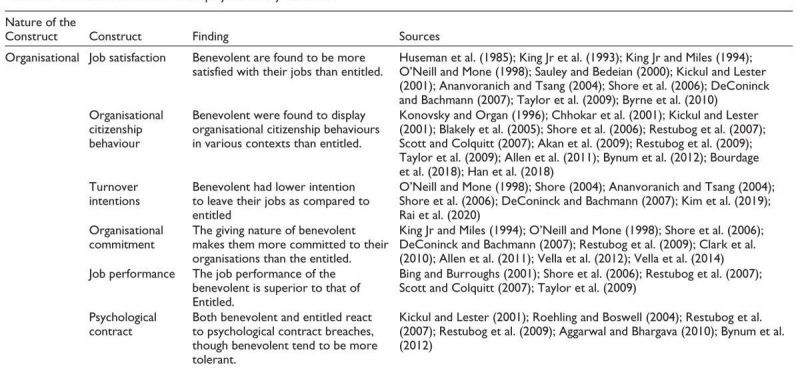

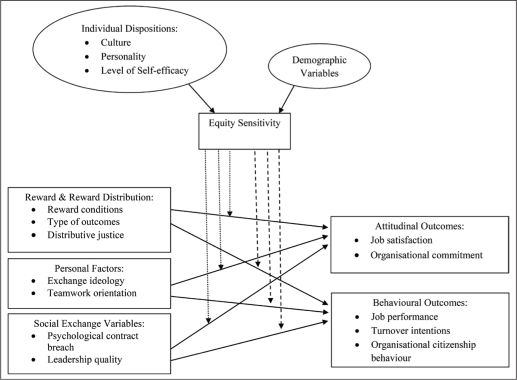

The articles were then analysed for their content. The authors independently reviewed the papers to identify the constructs and perspectives being studied in the domain. Each author provided codes to their analysis that were then compared and contrasted to reach a consensus. A thorough content analysis helped the authors identify the various theoretical perspectives that the articles adopted in the field. These perspectives are highlighted in Table 5.

Table 5. Theoretical Perspectives in Reviewed Articles.

Further analysis helped in highlighting the constructs predominantly studied in the equity sensitivity field. This was done to single out the concepts or processes being studied the most. Table 6 presents the list of these constructs. As evident by the table, both the organisation-specific and the non-organisational constructs were found to be significantly focused on by the studies. Among the organisational constructs, job satisfaction and organisational citizenship behaviour are the most studied. Individual dispositions are prominently studied among the non-organisational constructs.

Table 6. Constructs Studied in the Equity Sensitivity Research.

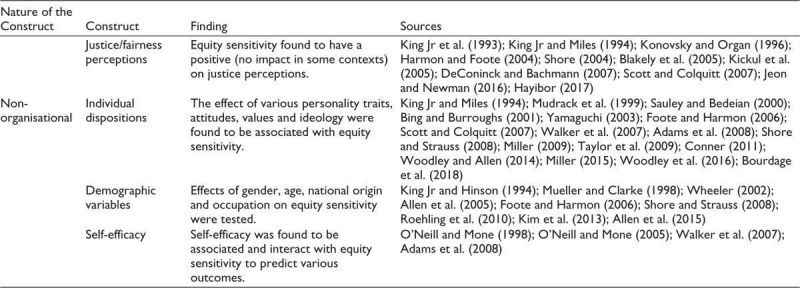

Based on the content analysis of the literature, a framework is collated which can be taken as the basis of future research in the field. Figure 6 presents the model. Being a typical individual difference variable, equity sensitivity has its grounding in the post-positivist paradigm due to its psychological nature and individual differences pertaining to contextual and demographic variables. Hence, the literature proposes that the sensitivity to equity that is, benevolence and entitlement will moderate the relationship between various reward systems, certain personal characteristics and social exchange variables which will then drive various positive or negative workplace attitudes and behaviour (Kumar & Agarwal, 2023). Equity sensitivity is affected by various demographic as well as individual disposition factors. These variables have been found to have an effect and interaction with equity sensitivity (Bourdage et al., 2018; Kim et al., 2013; O’Neill & Mone, 1998).

The moderating effects (Kumar et al., 2023b) of the differing equity sensitivity can be summarised as follows. Unlike the entitled individuals, the tolerant and ‘giving’ nature of the benevolent inclines them to display positive attitudes and behaviours in the work environment irrespective of the reward conditions (under reward or over reward) (King Jr et al., 1993). They are found to prefer intrinsic outcomes (Wheeler, 2007) and generally perceive distributive justice to exist in the reward distribution (Blakely et al., 2005). Additionally, due to their giving ideology (King Jr & Miles, 1994) and their ability to work in teams (teamwork orientation) (Bing & Burroughs, 2001); they are more likely to depict positive perceptions towards organisational outcomes. Lastly, their benevolence forms tolerance towards contract breach (Roehling & Boswell, 2004) and leadership (exchange relationship and responsiveness) (Han et al., 2018; McLoughlin & Carr, 1997; Shore et al., 2006); leading to positive attitudes and behaviours towards the organisation.

Figure 6. Proposed Conceptual Framework.

Research Gaps

This section addresses the following research question: What are the research gaps in the equity sensitivity research? The reviewed articles were analysed to identify the research gaps and find the limitations in methodology, theoretical framework as well as study settings and samples. The authors identified two prominent conceptual gaps and three vital methodological gaps in effective equity sensitivity research.

Conceptual Limitations Lack of Consensus Around a Framework

The review pointed out the lack of a consensus around the framework and role of equity sensitivity. The reason behind this is twofold. First, a relatively small amount of equity sensitivity research is foundational in the sound theoretical framework, and most of this work focuses on either the behavioural impact of the sensitivity (Allen & White 2002; Parnell & Sullivan, 1992), psychological effects (Conner, 2011; King Jr et al., 1993; Naumann et al., 2002) or the refinement of the equity sensitivity instrument (Davison & Bing, 2008; King Jr & Miles, 1994; Sauley & Bedeian, 2000). While integrating a theory from conjoining fields may be the approach to model development (Bynum et al., 2012), the sensitivity model is perceived to be more complex than this. This complexity arises from the fact that the theory has its base in the perceptual psychology of an individual, which itself is a separate and relevant sub-field in the branch of cognitive psychology.

Second, a relatively large number of studies focus on solving problems (instead of building theory), inducing a variety of theories, many of which are not dominant in the equity sensitivity theory. Although this contributes significantly to the theory, its contribution towards the building of a sound model is limited. The extant literature proposes a moderating role of equity sensitivity, but the work has produced mixed results so far. Some studies established it as a moderator (O’Neill & Mone, 1998) whereas several others found little or no moderation effects (Bing & Burroughs, 2001; Scott & Colquitt, 2007). This has created more confusion than clarity around the role of the construct.

Ambiguity in the Conceptualisation

Our review has identified three prominent ambiguities in the conceptualisation of the equity sensitivity construct. First, ambiguity exists among the measurement scales of the equity sensitivity concept. Studies have continuously claimed one measure as superior to the others (Foote & Harmon, 2006; Shore & Strauss, 2008; Wheeler, 2007). While the sample selection was initially identified as the reason behind one scale being superior to the other, further studies used the same sample and proved otherwise. Such findings cast doubt not only on the effectiveness of the instruments but also the concept as a whole. Another issue identified is the response pattern of the respondents in the study. The plausible reason behind the unclear conceptualisation of equity sensitivity could be the social desirability bias in the response of the respondents. A total of eight articles (Davison & Bing, 2008; Miller, 2009; Scott & Colquitt, 2007) have highlighted this issue. Social desirability bias is the tendency of the respondents in the study to respond in a manner that they perceive to be acceptable in a social setting, and the response they think will put them in a favourable light. Respondents can manipulate the results due to desirability bias by giving benevolent responses when in reality, they adopt an entitled approach.

Second, the conceptualisation of the basic nature of equity sensitivity has still not found its place in the existent literature. The confusion of equity sensitivity being a trait or a state (Huseman et al., 1987), a situation-activated trait (Konovsky & Organ, 1996), attitude (Shore, 2004) as well as the intrinsic (vs extrinsic) nature (Wheeler, 2002) still persists. This is evident by the confounding interactions equity sensitivity has had with various constructs. When equity sensitivity was studied in different cultural settings, no definite relationship was established between the two constructs. Additionally, when other factors, say gender, were considered, the findings were sample-specific (Kim et al., 2013; King Jr & Hinson, 1994; Wheeler, 2002). Some of these findings were in contradiction with the generally established cultural-induced behaviours (Allen et al., 2005; Chhokar et al., 2001; Mueller & Clarke, 1998).

Third, while researchers have hinted at equity sensitivity being a multi-dimensional concept as opposed to the established uni-dimensional understanding (Bing et al., 2009; Taylor et al., 2009), this aspect was left unattended and has not been acknowledged in the recent research carried out in the field. A lack of clarity in these conceptualisations rob the managers to mould and predict the attitudinal and behavioural outcomes/organisational behaviour of the employees (Naumann et al., 2002).

Methodological Limitations Absence of Longitudinal Research

As mentioned above, all articles included in the review adopt a static point of view, creating a dearth of longitudinal research. It is believed that longitudinal research is necessary to analyse the stability and trends of the theory (Mueller & Clarke, 1998). With equity sensitivity being perception oriented, its dynamic nature needs to be analysed over a period of time. The dearth of longitudinal studies explicitly indicates that not much attention has been given to such dynamic changes. A significant number of researchers also find it difficult to establish a causal relationship between variables and equity sensitivity in a cross-sectional setting (Aggarwal & Bhargava, 2010; Kickul et al., 2005; Oren & Littman-Ovadia, 2013). The causal inferences drawn using cross-sectional study design do not implicate causality but imply inferences (Kickul & Lester, 2001). With researchers worried about the problem of common method variance due to the cross-sectional survey design (Kim et al., 2019), it brings us to our next barrier.

The Dominance of Quantitative Research

The review has identified various research methodologies used to examine equity sensitivity, and a significant number of studies have used quantitative tools. As discussed above, applying quantitative research to study a field that lacks a proper framework to explain its underlying mechanism generally provides ambiguous results (Shore & Strauss, 2008; Wheeler, 2007). It is beneficial to use qualitative methods concomitantly with the quantitative tools to understand the phenomenon (Shah & Corley, 2006). A limited number of articles extend the theory (King Jr & Hinson, 1994), and others refine its applications (Bynum et al., 2012; Conner, 2011; Hayibor, 2017; O’Neill & Mone, 2005). While a substantial number of articles used the survey method as a tool to collect data, one problem underlying the survey method is that it is solely used for theory testing, which is the essence of scientific methodology, overlooking the significance that theory building and refinement holds (Shah & Corley, 2006). The cross-sectional survey method of data collection also carries the problem of common method variance/common method bias. Common method variance/bias refers to the variance attributable to the measurement method and not to the constructs that are being measured. A significant number of articles, a total of 20 (28%) studies, reported this problem.

Qualitative research approach could have significantly added value as it has immense potential to compliment quantitative approach by rendering depth and perspective to statistics (Kumar & Tuli, 2021). Having stemmed from human experiences, it could have thrown better light at the rationale for perceptual differences towards equity sensitivity. Qualitative research helps unfold the how and why (Sutton & Austin, 2015; Tuli et al., 2023b) of a behaviour, thus rendering better understanding that could have been utilised by organisations to create more equitable environment.

Limitations as to Sample Selection

The final limitation in the equity sensitivity research is the sample selection in the studies. Owing to the geographical bias where majority of the studies emanate from the USA and significant employment of the student sample, it becomes difficult to generalise the findings to the complete universe of research. The measurement scales for equity sensitivity have a wording that limits the equity sensitivity concept to an employer-employee relationship (Foote & Harmon, 2006). Thus, using a student sample for such purposes might not give effective results. Although a few studies used part-time working student samples, the selection still does not represent any individual’s perceptions and attitudes in a work environment.

As the literature indicates, the total distribution of studies reviewed are skewed, thus indicating the geographical sampling bias. It also highlights that the sampling effort is ‘spatially biased’, rather than equally distributed over the study area (Ross & Bibler-Zaidi 2019). Since, the geographical distribution was not a delimitation that the authors consciously made during the exclusionary and inclusionary decisions, neither did the authors have any intention to narrow the scope of the review, it represents a systematic bias introduced into the study design or instrument by the researcher (Price & Murnan, 2004). One reason of high number of studies in the USA could be credited to it being a high-income country with right consciousness among employees. Studies have also shown less accessibility of researches from other parts of the world causes limitation leading to geographical sampling bias (Zizka et al., 2021).

The significant variation in cultural aspects of the westernised developed economies and the Eastern emerging nations (Hofstede, 1984) clearly indicates that generalising the finding of one to another will be like comparing an apple with an orange. Besides this, the generalisability of management theories developed in one culture to other cultures has been seriously questioned in recent years. The literature has recommended the further testing of equity sensitivity in non-Western cultures (Ananvoranich & Tsang, 2004). This is because equity perceptions, by their very nature, are likely to be subject to cultural influences (Chhokar et al., 2001). Such geographical bias has also been found to affect the knowledge production and diffusion process, with the developed high-income countries being the producers and the middle- and low-income countries being mere receivers of such knowledge (Skopec et al., 2020).

Discussion

The current review aimed to revive the equity sensitivity theory by highlighting the developments in the field, collating a conceptual framework largely missing from the existing literature and identifying the research gaps in the existing body of literature on equity sensitivity. This article used the SLR method and reviewed a total of 74 published articles to highlight the gaps in the theoretical base, research settings and sample selection in equity sensitivity research. In this regard, this review identified two conceptual and three methodological limitations in the existent literature. The lack of consensus around the theoretical framework and role of the construct accompanied by the ambiguous conceptualisation poses gaps in the theory’s conceptual base. The findings indicate that, theoretically, equity sensitivity is underdeveloped and stark ambiguity exists in the existing research. While a significant number of studies induced a variety of theories secondary to the idea of equity sensitivity, hinting at broadening the interest of researchers from different fields, this does not contribute towards the development of the core theory. After all, theory building and refinement has equal importance as theory testing (Shah & Corley, 2006).

This theory witnessed many quantitative studies that contribute to the idea but lay no foundation to the theory development. Thus, an increase in the exploratory research practices to build a solid and stable theoretical understanding will be beneficial before performing any confirmatory analysis. To induce stability in the theory, longitudinal studies, which are currently missing from the existing literature body, need to be stressed upon. By identifying the research gaps, this review aims to direct all future studies towards overcoming the shortcomings in this field to aid in the development of the theory.

This review focused on providing a specific number of studies in one place due to the highly fragmented nature of the existing research. This will create awareness of the available research and help future researchers access the relevant literature. Another aim was to highlight the existing problems and inconsistencies that exist in the current research and raise questions around them. The collated framework depicting equity sensitivity’s relationship with other constructs will help in reviving the concept and guiding the future research in the field. To keep the scope limited, this review succeeded in including variant studies but can only act as an abridgement to the various gaps in the literature. Future research should aim at going deeper into the gaps identified.

Limitations

While identifying the limitations in the existing literature, the authors do not fail to acknowledge their review’s limitations. To uphold the quality of the reviewed articles and make the review comprehensive, academic articles from six distinct databases covering a variety of journals were included. The inclusion of published articles, though, ignores the latest research, which adds to the cumulative knowledge of the field. To eradicate any unpremeditated biases, transparency and evidence-based analysis were stressed upon.

Future Research Directions

Addressing the shortcomings in the existing body of literature as identified by the review provides a direction for future research. First, the influence of external factors (Ananvoranich & Tsang, 2004; Conner, 2011) as well as the work environment (Kim et al., 2019; Roehling et al., 2010) on the equity sensitivity of an individual can enhance the conceptualisation of the equity domain, and hence can be a direction for future research. Second, the future researchers must undertake cross-cultural research with equity sensitivity to solidify the relationship between the two constructs and increase the generalisation of the findings (Allen et al., 2005; Wheeler, 2002). Third, the ‘dark side’ of the equity sensitivity of an individual must be studied more to develop a holistic conceptual understanding of the construct and enhance the role of individual differences in guiding specific behaviours and/or traits (Woodley & Allen, 2014). Fourth, the intensity of the impact of equity sensitivity on the attitudinal and behavioural work-related outcomes, and how such an impact differs between the benevolent and the entitled (Kickul & Lester, 2001) can be another avenue for future research. Last, equity sensitivity is a psychological phenomenon influenced by context and demography (Huseman et al., 1987; Mudrack et al., 1999), having its roots in the post-positivist paradigm. The existing research in this domain complements the paradigmatic approach. Currently, the concept has a production-based orientation (input/output ratio), but it has to be looked at from other perspectives and lenses. For instance, the studies focusing on the sex-related differences in equity orientation in the workplace, have evolved with the findings showing the changing orientations towards workplace equity among the females (Kim et al., 2013; Major et al., 1989). Thus, looking at the domain from a feminist paradigm will facilitate in understanding this evolution in the equity sensitivity. Additionally, an interpretivist approach would enable an understanding of the ‘why’ part of the process as opposed to the existing ‘what’ and ‘how’ of the equity sensitivity. Since, it is an individual difference, it is affected by the social environment. Thus, an interpretivist lens might also develop an understanding on whether these equity orientations in the workplace transfer to the other contexts in which an individual operates or vice-versa.

In addition to the aforementioned future research directions, the authors propose further avenues to address the existing gaps in the body of literature on equity sensitivity. These are elaborated below.

Enhancing the Conceptual Foundation

The theory suffers from the limitation to classify equity sensitivity as a state or a trait (Huseman et al., 1987). With no empirical evidence addressing this issue, the theoretical underpinning of equity sensitivity still remains ambiguous. This calls for a deeper investigation to determine its nature wherein a longitudinal study might fulfil the said purpose. Additionally, qualitative research will thereby enhance the building of a framework (Shah & Corley, 2006). Further, it is imperative to address the contradictions that exist in theory to conceptualise the construct. For instance, Foote and Harmon (2006) failed to establish convergent validity between the two widely used measures of equity sensitivity. Thus, future researchers need to solidify such instruments’ effectiveness to cater to the shortcomings in the field.

Since equity sensitivity research is primarily conducted in the work environment, the prevalence of socially desirable responses is preeminent. Future research must make provisions to control for this aspect while analysing the data collected. Another area that future research needs to address includes the multi-dimensional nature of equity sensitivity which is proven by the changing relationship of the construct with various individual dispositions and demographic variables (Wheeler, 2002; Woodley et al., 2016). Thus, the construct must be studied in various situational contexts to clearly establish its multi-dimensionality, which is currently lacking in the literature.

Addressing the Methodological Shortcomings

Future research must reduce its dependence on the survey method of data collection and adopt more qualitative tools to understand whether the variance is a result of the constructs being studied or the measurement scale being used. This will aid in better understanding of the relationships between the construct and other behavioural and psychological variables. Future researchers must focus on the sample outside of the USA to increase the generalisation of their findings. Further, since the instruments to measure equity sensitivity are designed to study work relationships (Foote & Harmon, 2006), the use of a non-student sample must be undertaken unless a new dynamic measurement scale is developed.

Managerial Implications

Equity theory has been known to understand the perceptions of individuals regarding equitable treatment in their respective workplaces (Adams, 1965). Thus, the research on this theory has been prolific. On the other hand, equity sensitivity theory, which has enhanced the equity theory’s predictive power (Huseman et al., 1987), has been underdeveloped despite its practical value. But it is essential to emphasise the workforce’s equity sensitivity perceptions for the effective and efficient working of the organisation. Globalisation and high diversity among the workforce are some of the contemporary issues in today’s labour management, which marks the necessity of equity perceptions to be understood in depth (Kim et al., 2013; Yamaguchi, 2003). The comprehension of how the equity perceptions affect and formulate attitudes towards the workplace stimuli will aid in designing conducive compensation policies (Parnell & Sullivan, 1992). Additionally, the importance of equity sensitivity as an individual difference variable persists due to the dynamic social system that an organisation is and the value that such variables provide in comprehending the workplace attitudes and outcomes (Bourdage et al., 2018; Miller, 2015) as corroborated by the existing literature. Thus, the review can provide insights to the managers on what has been found till now and where they need to focus. It also highlights what is missing and where do they need to go.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Dr Sajeet Pradhan and Dr Richard Allen for their friendly reviews on the draft. They would also like to thank Mr Deepak Bhaskar for editing and formatting of the document.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Nikhita Tuli  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5854-4084

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5854-4084

Adams, J. S. (1963). Towards an understanding of inequity. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 67(5), 422–436.

Adams, J. (1965). Inequity in social exchange. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 267–299). Academic Press.

Adams, G. L., Treadway, D. C., & Stepina, L. P. (2008). The role of dispositions in politics perception formation: The predictive capacity of negative and positive affectivity, equity sensitivity, and self-efficacy. Journal of Managerial Issues, 20(4), 545–563.

Aggarwal, U., & Bhargava, S. (2010). The effects of equity sensitivity, job stressors and perceived organizational support on psychological contract breach. Vision, 14(1–2), 45–55.

Akan, O. H., Allen, R. S., & White, C. S. (2009). Equity sensitivity and organizational citizenship behaviour in a team environment. Small-Group Research, 40(1), 94–112.

Allen, R. S., Allen, D. E., Karl, K., & White, C. S. (2015). Are millennials really an entitled generation? An investigation into generational equity sensitivity differences. Journal of Business Diversity, 15(2), 14–26.

Allen, R. S., Evans, W. R., & White, C. S. (2011). Affective organizational commitment and organizational citizenship behavior: examining the relationship through the lens of equity sensitivity. Organization Management Journal, 8(4), 218–228.

Allen, R. S., Takeda, M., & White, C. S. (2005). Cross-cultural equity sensitivity: a test of differences between the United States and Japan. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 20(8), 641–662.

Allen, R. S., & White, C. S. (2002). Equity sensitivity theory: A test of responses to two types of under-reward situations. Journal of Managerial Issues, 14(4), 435–451.

Ananvoranich, O., & Tsang, E. W. (2004). The Asian financial crisis and human resource management in Thailand: The impact on equity perceptions. International Studies of Management & Organization, 34(1), 83–103.

Bing, M. N., & Burroughs, S. M. (2001). The predictive and interactive effects of equity sensitivity in teamwork-oriented organizations. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 22(3), 271–290.

Bing, M. N., Davison, H. K., Garner, B. L., Ammeter, A. P., & Novicevic, M. M. (2009). Employee relations with their organization: The multidimensionality of the equity sensitivity construct. International Journal of Management, 26(3), 436–444.

Blakely, G. L., Andrews, M. C., & Moorman, R. H. (2005). The moderating effects of equity sensitivity on the relationship between organizational justice and organizational citizenship behaviors. Journal of Business and Psychology, 20(2), 259–273.

Bourdage, J. S., Goupal, A., Neilson, T., Lukacik, E. R., & Lee, N. (2018). Personality, equity sensitivity, and discretionary workplace behavior. Personality and Individual Differences, 120, 144–150.

Bynum, L. A., Bentley, J. P., Holmes, E. R., & Bouldin, A. S. (2012). Organizational citizenship behaviors of pharmacy faculty: Modeling influences of equity sensitivity, psychological contract breach, and professional identity. Journal of Leadership, Accountability and Ethics, 9(5), 99–111.

Byrne, Z. S., Miller, B. K., & Pitts, V. E. (2010). Trait entitlement and perceived favorability of human resource management practices in the prediction of job satisfaction. Journal of Business and Psychology, 25(3), 451–464.

Carrell, M. R., & Dittrich, J. E. (1978). Equity theory: The recent literature, methodological considerations, and new directions. Academy of Management Review, 3(2), 202–210.

Chhokar, J. S., Zhuplev, A., Fok, L. Y., & Hartman, S. J. (2001). The impact of culture on equity sensitivity perceptions and organizational citizenship behavior: A five-country study. International Journal of Value-Based Management, 14(1), 79–98.

Clark, L. A., Foote, D. A., Clark, W. R., & Lewis, J. L. (2010). Equity sensitivity: A triadic measure and outcome/input perspectives. Journal of Managerial Issues, 22(3), 286–305.

Conner, D. S. (2011). Democratic legitimacy: A cross-cultural, equity sensitivity perspective of the acceptance of democratic ideals. Franklin Business & Law Journal, (4).

Davison, H. K., & Bing, M. N. (2008). The multidimensionality of the equity sensitivity construct: Integrating separate benevolence and entitlement dimensions for enhanced construct measurement. Journal of Managerial Issues, 20(1), 131–150.

Deconinck, J., & Bachmann, D. (2007). The impact of equity sensitivity and pay fairness on marketing managers’ job satisfaction, organizational commitment and turnover intentions. Marketing Management Journal, 17(2), 134–141.

Foote, D. A., & Harmon, S. (2006). Measuring equity sensitivity. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 21(2), 90–108.

Han, Y., Sears, G., & Zhang, H. (2018). Revisiting the “give and take” in LMX: Exploring equity sensitivity as a moderator of the influence of LMX on affiliative and change-oriented OCB. Personnel Review, 47(2), 555–571.

Harmon, S. K., & Foote, D. A. (2004). The influence of price difference and equity sensitivity on customer satisfaction in a dynamic pricing environment. ACR North American Advances.

Hayibor, S. (2017). Is fair treatment enough? Augmenting the fairness-based perspective on stakeholder behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 140(1), 43–64.

Hofstede, G. (1984). Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values. Sage.

Huseman, R. C., Hatfield, J. D., & Miles, E. W. (1985). Test for individual perceptions of job equity: Some preliminary findings. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 61(3), 1055–1064.

Huseman, R. C., Hatfield, J. D., & Miles, E. W. (1987). A new perspective on equity theory: The equity sensitivity construct. Academy of Management Review, 12(2), 222–234.

Jeon, G., & Newman, D. A. (2016). Equity sensitivity versus egoism: A reconceptualization and new measure of individual differences in justice perceptions. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 95–96, 138–155.

Kickul, J., Gundry, L. K., & Posig, M. (2005). Does trust matter? The relationship between equity sensitivity and perceived organizational justice. Journal of Business Ethics, 56(3), 205–218.

Kickul, J., & Lester, S. W. (2001). Broken promises: Equity sensitivity as a moderator between psychological contract breach and employee attitudes and behavior. Journal of Business and Psychology, 16(2), 191–217.

Kim, C. Y., Lee, J. H., & Shin, S. Y. (2019). Why are your employees leaving the organization? The interaction effect of role overload, perceived organizational support, and equity sensitivity. Sustainability, 11(3), 1–10.

Kim, D., Yang, C., & Lee, J. (2013). Equity sensitivity and gender differences. Indian Journal of Gender Studies, 20(3), 373–392.

King, W. C. Jr., & Hinson, T. D. (1994). The influence of sex and equity sensitivity on relationship preferences, assessment of opponent, and outcomes in a negotiation experiment. Journal of Management, 20(3), 605–624.

King, W. C. Jr., & Miles, E. W. (1994). The measurement of equity sensitivity. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 67(2), 133–142.

King, W. C. Jr., Miles, E. W., & Day, D. D. (1993). A test and refinement of the equity sensitivity construct. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 14(4), 301–317.

Konovsky, M. A., & Organ, D. W. (1996). Dispositional and contextual determinants of organizational citizenship behaviour. Journal of Organizational Behaviour, 17(3), 253–266.

Kumar, H. (2022). Augmented reality in online retailing: A systematic review and research agenda. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 50(4), 537–559.

Kumar, H., Gupta, P., & Chauhan, S. (2023a). Meta-analysis of augmented reality marketing. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 41(1), 110–123.

Kumar, H., & Agarwal, M. N. (2023). Filtering the reality: Exploring the dark and bright sides of augmented reality–based filters on social media. Australian Journal of Management, 03128962231199356.

Kumar, H., & Tuli, N. (2021). Decoding the branded app engagement process: A grounded theory approach. Asia Pacific Journal of Information Systems, 31(4), 582–605.

Kumar, H., Tuli, N., Singh, R. K., Arya, V., & Srivastava, R. (2023b). Exploring the role of augmented reality as a new brand advocate. Journal of Consumer Behaviour.

Major, B., Bylsma, W. H., & Cozzarelli, C. (1989). Gender differences in distributive justice preferences: The impact of domain. Sex Roles, 21(7), 487–497.

McLoughlin, D., & Carr, S. C. (1997). Equity sensitivity and double demotivation. The Journal of Social Psychology, 137(5), 668–670.

Miles, E. W., Hatfield, J. D., & Huseman, R. C. (1989). The equity sensitivity construct: Potential implications for worker performance. Journal of Management, 15(4), 581–588.

Miles, E. W., Hatfield, J. D., & Huseman, R. C. (1994). Equity sensitivity and outcome importance. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 15(7), 585–596.

Miller, B. K. (2009). Confirmatory factor analysis of the equity preference questionnaire. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 24(4), 328–347.

Miller, B. K. (2015). Entitlement and conscientiousness in the prediction of organizational deviance. Personality and Individual Differences, 82, 114–119.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & Prisma Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. International Journal of Surgery, 8(5), 336–341.

Mudrack, P. E., Mason, E. S., & Stepanski, K. M. (1999). Equity sensitivity and business ethics. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 72(4), 539–560.

Mueller, S. L., & Clarke, L. D. (1998). Political-economic context and sensitivity to equity: Differences between the United States and the transition economies of Central and Eastern Europe. Academy of Management Journal, 41(3), 319–329.

Naumann, S. E., Minsky, B. D., & Sturman, M. C. (2002). The use of the concept “entitlement” in management literature: A historical review, synthesis, and discussion of compensation policy implications. Human Resource Management Review, 12(1), 145–166.

O’Neill, B. S., & Mone, M. A. (1998). Investigating equity sensitivity as a moderator of relations between self-efficacy and workplace attitudes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83(5), 805–816.

O’Neill, B. S., & Mone, M. A. (2005). Psychological influences on referent choice. Journal of Managerial Issues, 17(3), 273–292.

Oren, L., & Littman-Ovadia, H. (2013). Does equity sensitivity moderate the relationship between effort–reward imbalance and burnout. Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 26(6), 643–658.

Otaye-Ebede, L., Sparrow, P., & Wong, W. (2016). The changing contours of fairness: Using multiple lenses to focus the HRM research agenda. Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance, 3(1), 70–90.

Parnell, J. A., & Sullivan, S. E. (1992). When money isn’t enough: The effect of equity sensitivity on performance-based pay systems. Human Resource Management Review, 2(2), 143–155.

Price, J. H., & Murnan, J. (2004). Research limitations and the necessity of reporting them. American Journal of Health Education, 35(2), 66.

Pritchard, R. D. (1969). Equity theory: A review and critique. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 4(2), 176–211.

Rai, S., Megyeri, E., & Kazár, K. (2020). The impact of equity sensitivity on mental health, innovation orientation, and turnover intention in the Hungarian and Indian contexts. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 9(4), 1044–1062.

Restubog, S. L. D., Bordia, P., & Bordia, S. (2009). The interactive effects of procedural justice and equity sensitivity in predicting responses to psychological contract breach: An interactionist perspective. Journal of Business and Psychology, 24(2), 165–178.

Restubog, S. L. D., Bordia, P., & Tang, R. L. (2007). Behavioural outcomes of psychological contract breach in a non-western culture: The moderating role of equity sensitivity. British Journal of Management, 18(4), 376–386.

Roehling, M. V., & Boswell, W. R. (2004). “Good cause beliefs” in an “at-will world”? A focused investigation of psychological versus legal contracts. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 16(4), 211–231.

Roehling, M. V., Roehling, P. V., & Boswell, W. R. (2010). The potential role of organizational setting in creating “entitled” employees: An investigation of the antecedents of equity sensitivity. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 22, 133–145.

Ross, P. T., & Bibler Zaidi, N. L. (2019). Limited by our limitations. Perspectives on Medical Education, 8(4), 261–264.

Sass, M. D., Liao-Troth, M. A., & Wonder, B. D. (2011). Determining person–organization fit for healthcare CEOs: How executive equity sensitivity relates to nonprofit and for-profit sector selection. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 22(2), 199–216.

Sauley, K. S., & Bedeian, A. G. (2000). Equity sensitivity: Construction of a measure and examination of its psychometric properties. Journal of Management, 26(5), 885–910.

Scott, B. A., & Colquitt, J. A. (2007). Are organizational justice effects bounded by individual differences? An examination of equity sensitivity, exchange ideology, and the Big Five. Group & Organization Management, 32(3), 290–325.

Shah, S. K., & Corley, K. G. (2006). Building better theory by bridging the quantitative–qualitative divide. Journal of Management Studies, 43(8), 1821–1835.

Shore, T. H. (2004). Equity sensitivity theory: Do we all want more than we deserve? Journal of Managerial Psychology, 19(7), 722–728.

Shore, T. H., & Strauss, J. (2008). Measurement of equity sensitivity: A comparison of the equity sensitivity instrument and equity preference questionnaire. Psychological Reports, 102(1), 64–78.

Shore, T., Sy, T., & Strauss, J. (2006). Leader responsiveness, equity sensitivity, and employee attitudes and behavior. Journal of Business and Psychology, 21(2), 227–241.

Skopec, M., Issa, H., Reed, J., & Harris, M., 2020. The role of geographic bias in knowledge diffusion: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. Research Integrity and Peer Review, 5(1), 1–14.

Sutton, J., & Austin, Z. (2015). Qualitative research: Data collection, analysis, and management. The Canadian Journal of Hospital Pharmacy, 68(3), 226–231.

Taylor, S. G., Kluemper, D. H., & Sauley, K. S. (2009). Equity sensitivity revisited: Contrasting unidimensional and multi-dimensional approaches. Journal of Business and Psychology, 24(3), 299–314.

Tranfield, D., Denyer, D., & Smart, P. (2003). Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. British Journal of Management, 14(3), 207–222.

Tuli, N., Kumar, H., Srivastava, R., & Gupta, P. (2023a). Demystifying the engagement process: A BoP perspective toward social media engagement. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 1–18.

Tuli, N., Shrivastava, K., & Khattar, D. (2023b). Understanding equity sensitivity through the lens of personality: A review of associations and underlying nature. Management Research Review, 46(9), 1261–1277.

Tuli, N., Srivastava, R., & Kumar, H. (2023c). Navigating services for consumers with disabilities: A comprehensive review and conceptual framework. Journal of Services Marketing, ahead-of-print.

Vella, J., Caruana, A., & Pitt, L. F. (2012). Perceived performance, equity sensitivity and organizational commitment among bank managers. Journal of Financial Services Marketing, 17(1), 5–18.

Vella, J., Caruana, A., & Pitt, L. F. (2014). Elements of a talent strategy for effective relationship building: A study among bank sales and service providers. Journal of Financial Services Marketing, 19(2), 118–131.

Walker, H. J., Feild, H. S., Giles, W. F., Bernerth, J. B., & Jones-Farmer, L. A. (2007). An assessment of attraction toward affirmative action organizations: Investigating the role of individual differences. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 28(4), 485–507.

Walster, E., Berscheid, E., & Walster, G. W. (1973). New directions in equity research. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 25(2), 151–176.

Weick, K. E. (1966). The concept of equity in the perception of pay. Administrative Science Quarterly, 11(3), 414-–439.

Wheeler, K. G. (2002). Cultural values in relation to equity sensitivity within and across cultures. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 17(7), 612–627.

Wheeler, K. G. (2007). Empirical comparison of equity preference questionnaire and equity sensitivity instrument in relation to work outcome preferences. Psychological Reports, 100(3), 955–962.

Woodley, H. J., & Allen, N. J. (2014). The dark side of equity sensitivity. Personality and Individual Differences, 67, 103–108.

Woodley, H. J., Bourdage, J. S., Ogunfowora, B., & Nguyen, B. (2016). Examining equity sensitivity: An investigation using the Big Five and HEXACO models of personality. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1–15.

Yamaguchi, I. (2003). The relationships among individual differences, needs and equity sensitivity. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 18(4), 324–344.

Zizka, A., Antonelli, A., & Silvestro, D. (2021). Sampbias, a method for quantifying geographic sampling biases in species distribution data. Ecography, 44(1), 25–32.