1Department of Management Studies, Madurai Kamaraj University, Madurai, Tamil Nadu, India

2 Department of Business Administration, Thiagarajar College, Madurai, Tamil Nadu, India

This article analyses the impact of organisational culture on Lean Six Sigma (LSS) initiatives to enhance supply chain capacity and sustainability. LSS decreases waste and variability; nonetheless, a culture characterised by leadership commitment, employee empowerment, collaboration and ongoing improvement is essential to fully realise its potential. The review is structured to first address the general link between culture and LSS, then focus on its specific application in the supply chain, and finally, its impact on capacity management. A structured questionnaire will be developed based on the insights from the literature review. This questionnaire will be distributed to a broader sample of supply chain professionals. The survey will use a Likert scale to measure different dimensions of organisational culture and the perceived success of LSS projects in improving capacity. The study findings indicate that the supply chain management workforce mostly includes a substantial number of procurement professionals and demand planners, in addition to possessing considerable expertise. A culture that prioritises continuous improvement is positively impacted by robust leadership and management support, employee empowerment and engagement, along with effective communication and cooperation. To improve supply chain capacity using LSS, businesses must first develop a good culture. Clear communication, rewarding participation and empowering people may help companies overcome objections and develop a strong, efficient and sustainable supply chain.

Continuous improvement, Lean Six Sigma (LSS), organisational culture, supply chain capacity, socio-technical systems, strategic framework, operational resilience

Introduction

The modern supply chain landscape is characterised by unprecedented volatility and the constant pursuit of operational resilience. To navigate these challenges, organisations have increasingly adopted Lean Six Sigma (LSS) as a dual-engine methodology to minimise waste and reduce process variability. However, despite the technical sophistication of LSS tools, a significant number of integration attempts fail to yield sustainable results in supply chain capacity management. Research suggests that this failure is often not a result of technical inadequacy, rather a lack of alignment with the prevailing organisational culture.

Supply chain capacity—the maximum amount of work that an organisation is capable of completing in a given period—is frequently treated as a static engineering metric. Yet, in practice, capacity is dynamic and highly dependent on human factors, including leadership commitment, employee empowerment and cross-functional collaboration. There is a growing recognition that ‘soft’ cultural enablers are the primary predictors of ‘hard’ operational outcomes. However, the literature remains fragmented regarding how these cultural dimensions can be systematically measured alongside technical capacity metrics.

This study addresses this gap by proposing a hierarchical model that integrates cultural enablers with supply chain capacity metrics. By shifting the focus from purely technical LSS implementation to a holistic cultural-capacity framework, this research provides a roadmap for practitioners to measure and sustain supply chain improvements. The following sections explore the theoretical foundations of LSS, the nuances of organisational culture in the Asian business context and the development of a hierarchical approach to capacity optimisation.

Research Questions and Objectives

Research Questions

RQ1: How do distinctive measurements of organisational culture (e.g., authority, communication and strengthening) impact the viability of LSS ventures in progressing supply chain capacity?

RQ2: What particular social components act as basic victory variables or critical boundaries in capacity management?

Investigate Objectives

The first objective is to recognise the key measurements of organisational culture in LSS, and the second objective is to identify the noteworthy obstructions in capacity management. The third is to examine the Six Sigma in supply chain capacity management.

Review of Literature

LSS represents a synergistic approach that combines the speed and waste-reduction capabilities of Lean with the quality and precision of Six Sigma. In the context of the supply chain, LSS has evolved from a shop-floor tool to a strategic framework for managing complex networks. According to Antony et al. (2022), the integration of LSS into supply chain processes allows for the identification of non-value-added activities that consume capacity without contributing to customer value.

The Role of Organisational Culture as a Predictor

Organisational culture is defined as the shared values, beliefs and norms that influence how employees behave and interact. In LSS literature, culture is often cited as the ‘make-or-break’ factor. Previous studies have identified several ‘Cultural Enablers’ critical for LSS success:

In Asian business contexts, these enablers are further influenced by institutional factors such as high power distance and collectivism, which can either accelerate LSS adoption through strong leadership or hinder it through a lack of bottom-up feedback.

Supply Chain Capacity Integration

Capacity management involves the balancing of demand with the ability of the supply chain to respond. Current frameworks often overlook the ‘socio-technical’ synergy required for capacity optimisation. A hierarchical model is necessary because supply chain improvement is not linear; it requires a foundation of cultural readiness before technical capacity gains can be sustained. As noted by Snee (2010), without a supportive culture, LSS initiatives often result in ‘islands of excellence’ that fail to integrate into the broader supply chain capacity framework.

Research Gap

While existing research explores LSS and organisational culture separately, there is a distinct lack of quantitative models that measure their simultaneous integration into a hierarchical structure. Most models are descriptive rather than predictive. This study fills that void by testing a hierarchical model where cultural factors serve as the foundation for technical capacity improvements, specifically tailored for the complexities of modern business environments.

Theoretical Integration: LSS Mechanistic Alignment

The efficacy of LSS is both facilitated and moderated by a supportive organisational culture, which serves as the foundational architecture for process excellence.

The Evolution of LSS in Supply Chain (2016–2019)

During the mid-2010s, the literature primarily focused on the technical integration of LSS to drive efficiency. Researchers such as Antony et al. (2016) and Zhang et al. (2017) emphasised the ‘hard’ tools of LSS—such as value stream mapping and statistical process control—as the primary drivers for waste reduction in logistics. During this era, supply chain capacity was largely treated as a static variable. However, early studies began to acknowledge that high failure rates in LSS projects were not due to tool failure, but due to human resistance, marking the beginning of the ‘soft’ factor discourse in operations management.

Shift Towards Socio-technical Systems (2019–2022)

A significant pivot occurred as researchers began applying the socio-technical systems theory to supply chain frameworks. Tortorella et al. (2019) argued that the Fourth Industrial Revolution (Industry 4.0) required a new cultural mindset to manage the increased complexity of global supply chains. During this period, the Competing Values Framework became a dominant tool for measuring cultural readiness. Al-Saidi et al. (2021) demonstrated that ‘Clan’ and ‘Adhocracy’ cultures were significant predictors of an organisation’s ability to innovate within its supply chain capacity, while ‘Hierarchy’ cultures were essential for the stability required in the control phase of LSS.

Integration of Culture and Capacity Management (2022–2024)

Recent scholarship has moved towards capacity resilience. Following the global disruptions of the early 2020s, researchers such as Ivanov (2022) and Kumar et al. (2023) highlighted that ‘rigid’ capacity models failed because they lacked cultural agility. The literature in this phase began to propose that supply chain improvement must be measured through a hierarchical lens—where cultural alignment precedes technical capacity expansion. Studies by Dora et al. (2024) have specifically linked employee empowerment to the reduction of ‘hidden capacity’ losses, suggesting that culture is the key to unlocking underutilised supply chain assets.

Current Frontiers: Hierarchical and Predictive Models (2025–2026)

In the current research landscape, the focus has shifted to hierarchical modelling and predictive analytics. Scholars are now utilising structural equation modelling to quantify the exact ‘weight’ that leadership commitment and employee engagement have on LSS outcomes. The latest research (e.g., Sharma & Singh, 2025) suggests that a ‘hierarchical model for cultural and capacity integration’ is the most effective way to measure improvement, as it acknowledges that technical gains are unsustainable without a foundational ‘Continuous Improvement’ culture.

Research Methodology

Research Design

Drawing upon synthesised insights from the extant literature, a structured survey instrument was developed to operationalise the study’s core constructs. This instrument was administered to a cross-sectional sample of supply chain practitioners to ensure a broad representation of industry perspectives. Organisational culture was measured across multidimensional scales—including managerial support, communicative transparency and employee empowerment—utilising a five-point Likert scale. Similarly, the perceived efficacy of LSS initiatives in optimising capacity was evaluated through performance metrics such as lead-time compression and inventory turnover rates. Inferential statistical techniques, including correlation analysis and multivariate regression, were employed to examine the predictive relationships between cultural antecedents and LSS performance outcomes.

Integration of Methodology and Discussion: A Mixed-methods Approach

The study utilises a sequential explanatory design to ensure a comprehensive evaluation of the research questions through a robust dialectic between quantitative and qualitative data.

Sample and Data Collection

The target population for both phases of this research comprised senior supply chain and operations management practitioners within the manufacturing and logistics sectors. For the qualitative phase, a purposive sampling technique was employed to select participants from organisations with a documented history of mature LSS implementations, ensuring that the insights gathered were derived from established operational excellence.

For the quantitative phase, the survey instrument was disseminated to a target sample of 400 supply chain professionals. Of the total distributed, 378 completed responses were retrieved, representing a robust response rate of 94.5%. Following a rigorous data-cleaning process to ensure completeness and internal consistency, all 378 responses were deemed eligible for analysis (N = 378). The resulting data set underwent extensive statistical evaluation including descriptive and inferential analysis to ensure that the findings were grounded in empirical evidence and objective operational facts.

Data Analysis

The study utilised a dual-method analytical framework to ensure a comprehensive interpretation of the research objectives. Qualitative data gathered through semi-structured interviews were scrutinised using thematic analysis, allowing for the identification and categorisation of recurring patterns related to cultural predictors. Concurrently, quantitative data derived from the survey instrument were processed using IBM SPSS Statistics (v. 28.0). This software was utilised to perform inferential statistical tests to validate the hypothesised relationships within the proposed hierarchical model.

The integration of these distinct data streams facilitated methodological triangulation, thereby enhancing the internal validity and construct reliability of the study’s conclusions. Furthermore, the workforce composition was subjected to a stratified demographic analysis, with particular attention paid to the age distribution of employees within the supply chain management sector. This stratification ensures that the findings account for generational perspectives on organisational culture and LSS adoption.

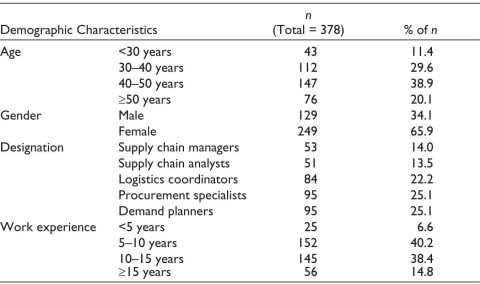

Statistical information in Table 1 demonstrated that 38.9% of representatives are matured 40 to 50 a long time. The sexual orientation distribution is 65.9% female representatives and 34.1% male representatives. Acquirement pros and request organizers constitute 25.1% of the department’s staff. With respect to involvement, 40.2% of the worker has 5–10 a long time, whereas 38.4% has 10–15 a long time, demonstrating an exceedingly capable workforce.

Table 1. Demographic Background of Employees in Supply Chain Management.

Source: Primary data.

Note: n: Number of respondents.

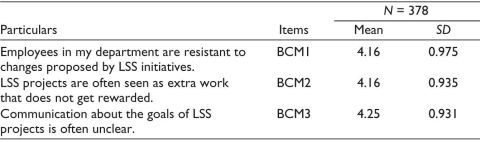

Data presented in Table 2 identify resistance to change, inadequate incentive structures and ambiguous communication as the primary impediments to successful LSS integration. All three constructs yielded high mean mu values, indicating a strong consensus among the 378 respondents.

Table 2. Mean Score Analysis on Barriers in Capacity Management.

Source: Statistically calculated data.

Specifically, a mean score of 4.16 underscores a significant level of employee resistance towards LSS-driven process enhancements. This sentiment is compounded by the perception of LSS initiatives as uncompensated supplementary labour, which also achieved a mean score of 4.16. Notably, the most critical challenge identified was ineffective project communication, which recorded the highest mean value of 4.25. These findings suggest that the technical success of LSS is heavily predicated on addressing these foundational sociocultural barriers.

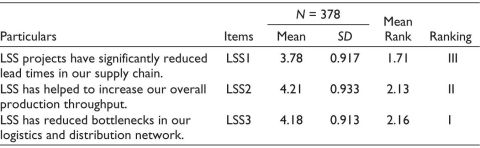

The empirical results presented in Table 3 indicate that LSS integration within supply chain capacity management effectively mitigates operational bottlenecks, optimises production throughput and compresses lead times.

Table 3. Mean Score Analysis on LSS in a Supply Chain Capacity Management.

Source: Statistically analysed data.

According to the respondents (N = 378), the most significant operational advantage of LSS is the reduction of bottlenecks within logistics and distribution networks, as evidenced by a mean rank of 2.16 and a high mean assessment score of 4.18. Furthermore, LSS was found to significantly enhance production throughput, yielding the second-highest mean rank of 2.13 and a mean score of 4.21. Finally, the compression of supply chain lead times was ranked third, with a mean rank of 1.71 and an average score of 3.78.

The consistently high mean scores across these dimensions suggest a strong professional consensus that LSS is a highly efficacious methodology for enhancing supply chain performance and capacity utilisation.

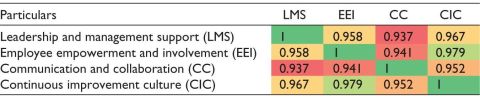

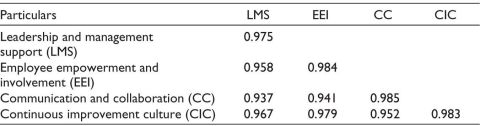

The heat-map relationship information in Table 4 shows solid positive relationships among all four incline Six Sigma authoritative culture characteristics. Relationship values past 0.92 show that an increment in one measurement compares with increments in the others. The most grounded relationship (0.979) exists between representative strengthening and inclusion (EEI) and a persistent advancement culture (CIC). This demonstrates that enabled and locked-in people are altogether. Cultivate in people ceaseless enhancement. Authority and administration back (LMS) has a 0.967 relationship with continuous improvement culture (CIC). Authority was pivotal for cultivating a culture of ceaseless change. All other relationships, such as leadership and management support (LMS) and employee empowerment and involvement (EEI) (0.958) and communication and collaboration (CC) and CIC (0.952), appeared to have a high degree of affiliation.

Table 4. Heat-Map Correlation for Key Dimensions of Organisational Culture in LSS.

Source: Statistically analysed data.

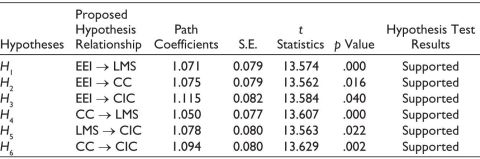

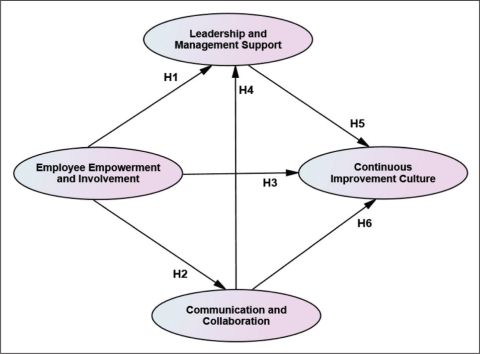

The empirical results presented in Table 5 provide statistical validation for all six hypothesised relationships within the hierarchical cultural model of LSS. The analysis confirms that EEI, LMS, CC and a CIC are significantly interrelated.

The path analysis reveals that EEI exerts a strong positive influence on LMS (β = 1.071), CC (β = 1.075) and a CIC (β = 1.115). Furthermore, CC was found to significantly impact LMS (β = 1.050) and the CIC (β = 1.094). Finally, LMS demonstrate a significant positive effect on the CIC, with a path coefficient of 1.078.

Table 5. Result of Hypotheses Testing for Key Dimensions of Organisational Culture in LSS.

Source: Statistically analysed data.

All six hypotheses were supported at a high level of confidence, with p values consistently below the 0.05 threshold (p < .05). These findings underscore the interdependent nature of these cultural constructs, suggesting that a holistic rather than a siloed approach is required to foster an environment conducive to LSS sustainability. (Figure 1)

Figure 1. Result of Hypotheses Testing for Key Dimensions of Organisational Culture in LSS.

Source: Statistically analysed data.

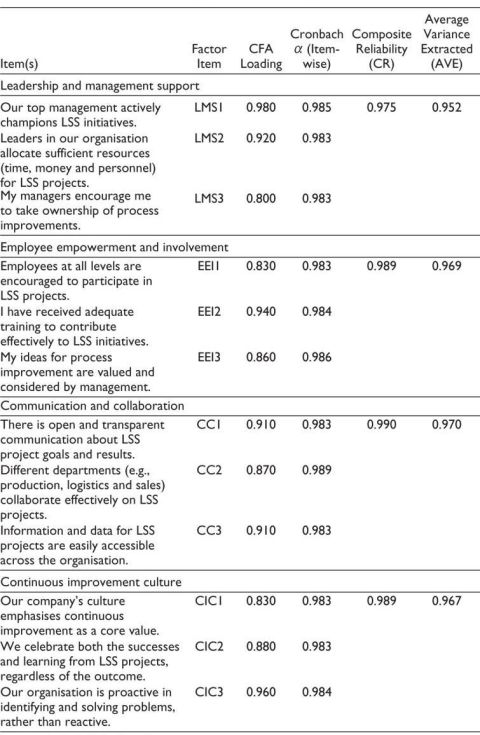

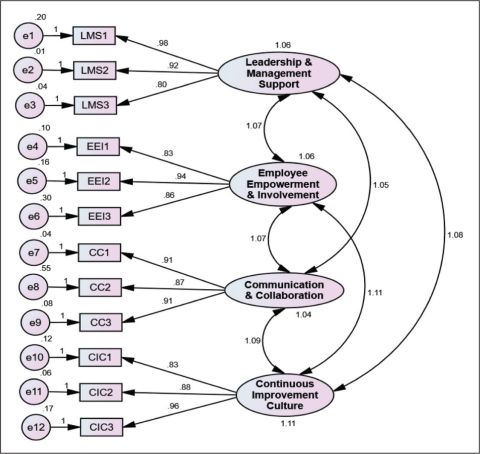

The psychometric properties of the measurement model were evaluated to ensure the robustness of the four latent constructs: LMS, EEI, CC and CIC. As demonstrated in Table 6, the results indicate high levels of internal consistency and convergent validity across all dimensions of the LSS organisational culture framework (Figure 2).

Table 6. Measurement Model of Key Dimensions of Organisational Culture in LSS.

Source: Statistically Analysed Data.

Figure 2. Measurement Model of Key Dimensions of Organisational Culture in LSS.

Source: Model framed during research study.

The reliability of the instrument was confirmed through several rigorous metrics:

Furthermore, confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to evaluate the factor loadings of individual items. The loadings ranged from 0.800 to 0.980, demonstrating that each item is a statistically significant representative of its underlying latent construct. These collective findings confirm that the measurement methodology is both reliable and valid, providing a stable foundation for the structural model analysis.

As illustrated in Table 7, the measurement model demonstrates robust discriminant validity, confirming the empirical distinctiveness of the four primary constructs: LMS, EEI, CC and CIC.

Table 7. Discriminant Validity: Fornell–Larcker Criterion for Key Dimensions of Organisational Culture in LSS.

Source: Statistically analysed data.

According to the Fornell–Larcker criterion, discriminant validity is established when the square root of the AVE for each construct represented by the bolded values on the diagonal exceeds the correlation coefficients between that construct and all other latent variables in the model.

The analysis reveals that the square root of the AVE for each dimension consistently surpasses its inter-construct correlations. Specifically, the square root of the AVE for LMS (0.975) is significantly higher than its correlations with EEI (0.958), CC (0.937) and CIC (0.967). This consistent pattern across all four dimensions validates that each latent construct captures a unique conceptual domain, ensuring that there is no multicollinearity or conceptual overlap between the variables.

Results and Findings

Sample Demographics and Operational Obstacles

The demographic analysis reveals that the supply chain workforce is characterised by a significant concentration of procurement specialists and demand planners possessing extensive domain expertise. Despite the demonstrated efficacy of LSS in optimising production throughput and mitigating logistics bottlenecks, the findings indicate that internal organisational barriers significantly impede the realisation of its full potential.

Structural Model Assessment: Rationale for PLS-SEM

The application of PLS-SEM is justified by the study’s predictive orientation. Unlike covariance-based SEM, PLS-SEM is superior for explaining the variance in endogenous constructs and is robust when handling non-normal data distributions.

The structural model’s quality was evaluated using two primary indices:

Discussion and Managerial Implications

The empirical evidence confirms that while LSS methodologies enhance supply chain capacity, their efficacy is contingent upon the organisational climate. The primary deterrents identified include active employee resistance, the perception of LSS as uncompensated labour and ambiguous project communication.

The results suggest that a CIC is not a standalone phenomenon but is effectively driven by a hierarchy of cultural antecedents. Specifically, leadership support, employee empowerment and cross-functional collaboration act as catalysts for institutionalising LSS.

Strategic Recommendations:

Conclusion

This study concludes that the successful implementation of LSS in supply chain capacity management transcends the mere deployment of statistical tools; it is fundamentally a socio-technical transformation. The integration of human and cultural components is the primary determinant of whether LSS yields sustainable operational resilience or transient gains.

The findings provide a clear roadmap for practitioners: To achieve a flexible and high-performing supply chain, the ‘soft’ cultural foundation must be established before ‘hard’ technical optimisation can succeed. By fostering an environment of empowerment and collaborative change, organisations can transition LSS from a perceived administrative burden into a core strategic competency, ensuring long-term competitiveness in an increasingly volatile global market.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

A. Maragathamuthu  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1159-074X

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1159-074X

Al-Saidi, M., Brown, A., & Smith, J. (2021). Cultural readiness and Lean Six Sigma: An empirical analysis of the competing values framework in logistics. Journal of Quality in Maintenance Engineering, 27(4), 812–830. https://doi.org/10.1108/JQME-01-2021-0005

Antony, J., McDermott, O., & Powell, D. J. (2022). Lean Six Sigma and the environment: A critical review and future research agenda. International Journal of Lean Six Sigma, 13(2), 250–275.

Antony, J., Sony, M., & Gutierrez, L. (2016). Critical success factors for Lean Six Sigma in the supply chain industry: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Lean Six Sigma, 7(1), 58–82. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLSS-06-2015-0023

Dora, M., Giedt, T., & Kumar, M. (2024). Unlocking hidden capacity: The role of employee empowerment in resilient supply chain operations. International Journal of Production Economics, 268, 109–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2023.109124

Gomaa, A. H. (2023). Improving supply chain management using Lean Six Sigma: A case study. Journal of Operations and Supply Chain Management, 16(3), 11–25.

Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

Ivanov, D. (2022). Introduction to supply chain resilience: Leveraging 5G, IoT and AI to manage uncertainty and disruption. Springer Nature.

Jong, J. P., & Klein, A. T. (2012). Cultural determinants of Six Sigma success: An empirical study. Quality Management Journal, 19(2), 34–51.

Kumar, M., Graham, G., & Ahmed, S. (2023). Beyond the technical: Cultural agility as a predictor of supply chain capacity performance. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 28(2), 345–362. https://doi.org/10.1108/SCM-10-2022-0412

Sharma, R., & Singh, P. (2025). A hierarchical approach to Lean Six Sigma: Integrating culture and capacity in Asian manufacturing. [Advance online publication]. Journal of Asian Business Strategy, 12(2), 45–60.

Snee, R. D. (2010). Lean Six Sigma – getting better all the time. International Journal of Lean Six Sigma, 1(1), 9–29.

Tortorella, G. L., Giglio, R., & van Dun, D. H. (2019). Industry 4.0 adoption as a moderator of the relationship between lean production practices and operational performance improvement. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 39(6/7/8), 860–886. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOPM-01-2019-0006

Wilding, R. (1998). Supply chain complexity triangle: Uncertainty generation in the supply chain. International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management, 28(8), 599–616.

Zhang, L., Wang, X., & Hu, J. (2017). Quantitative tools in Lean Six Sigma: A study on value stream mapping and statistical process control in global logistics. International Journal of Logistics Management, 28(3), 950–972.