1 Indian Institute of Management Bangalore (IIMB), Bengaluru, Karnataka India

2 Indian Institute of Technology Jodhpur (IITJ), Ratanada, Jodhpur, Rajasthan, India

Creative Commons Non Commercial CC BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License (http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-Commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed.

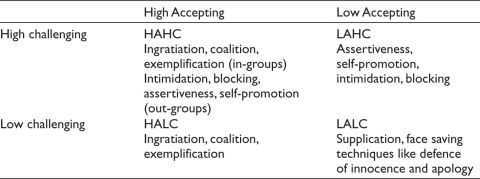

This article tries to extend the Framework for Impression Management by Women in India (FIMWI) by refining the conceptualisation of attitude towards gender stereotypes (ATGS). We try to explore the possible attitudes of women to gender stereotypes using the combinations of high or low accepting and challenging ATGS. Using these combinations, we identify four possible categories of responses to gender stereotypes, namely ‘High Accepting, High Challenging’ (HAHC), ‘Low Accepting, High Challenging’ (LAHC), ‘High Accepting, Low Challenging’ (HALC) and ‘Low Accepting, Low Challenging’ (LALC). Using the social identity theory, we explore the ways in which the ATGS would perhaps influence the choice of impression management tactics with in-group and out-group members. We further identify the potential impression management tactics that would be implemented by women in each of these categories. We propose that hard impression management techniques would be used for out-group members by women having the HAHC combination. They would use soft impression management techniques for in-group members. Hard impression management techniques would be used by women having the LAHC combination with in-group as well as out-group. Soft impression management techniques would be used by women having the HALC combination with in-group as well as out-group. Soft impression management techniques would be used by the women having LALC combination. Future research possibilities are suggested; practical implications are also discussed.

attitude towards gender stereotypes (ATGS), impression management, social identity theory, ingratiation, intimidation, supplication, coalition, blocking

Introduction

Impression Management

Impression management is a natural human behaviour. The social nature of human society increases the relevance of impression management in social contexts. With increasing prominence of organisations across the world, one of the common and prominent contexts where impression management has been studied is the workplace. Impression management could be defined as the process through which individuals use their ‘expressiveness’ to make ‘impressions’ on their ‘audience’, with the implication that the audience will constantly seek to decode these expressions (Goffman, 2010).

Despite the prevalence of impression management studies in other cultures, the cultural dimension has been considered rarely. On the contrary, it has been assumed that studies on impression management are the same everywhere (Bolino et al., 2016). The generalisation that impression management across cultures would be the same highlights a major gap in the research on impression management (Bolino et al., 2016). This article tries to address this gap by highlighting the nuances in the Indian context.

Gender Stereotypes and Attitude Towards Gender Stereotypes (ATGS)

Although ATGS has been studied across cultures, it has been less researched in the context of workplaces. This creates avenues for exploring ATGS in the Indian workplace. Within the purview of Indian workplaces, ATGS will help in understanding the reactions/responses to the prevailing gender stereotypes.

Research Question

This article attempts to extend the Framework for Impression Management by Women in India (FIMWI) framework by exploring the ATGS of women as an antecedent to the choice of impression management behaviours. In other words, this article attempts to answer the research question ‘How does ATGS influence impression management strategies used by women in their workplaces?’

Potential Contributions

Gender stereotypes and ATGS, therefore, form interesting variables for the purpose of research since it opens doors for exploring its various implications across different settings. There are some reasons as to how this study could contribute to the existing literature.

First, due to its focus on the aspects of impression management and ATGS in the Indian workplace, the article aims to understand how the relationship between these components would affect the Indian working women and pave way for bringing their narratives in the workspace to the forefront, something that the high-power distance nature of the Indian culture resists rather than promoting. Second, the focus on ATGS would provide the reader a chance to witness the receiving end of gender stereotypes. It would help the readers understand how women respond to gender stereotypes.

The implications of ATGS form an interesting avenue for research. Since it has already been established that attitude is a strong indicator of behaviour, ATGS will affect the decision-making process of women to a great extent. It would impact the decisions they make across all walks of life.

Being an important tool in the organisational atmosphere, the choice of impression management technique is a crucial decision to be made. This decision is influenced largely by one’s ATGS. This exploration will also contribute to the existing literature in the context of impression management.

We will try to ensure these contributions by reviewing past literature on impression management, ATGS and FIMWI, gender role theory and gender stereotypes. We will then try exploring a reconceptualised version of ATGS by combining high and low levels of accepting and challenging ATGS. After exploring the combinations of ATGS, we will try to understand the effect of the various combinations of ATGS on the choice of impression management behaviours adopted by women. We will also briefly explore the role played by social identity theory in moderating the effect of ATGS on choice of impression management behaviours.

Literature Review

Impression Management

Jones and Pittman (1982) identified five techniques that were associated with specific desired images. They were ‘ingratiation’ which could be used to be seen as likeable or friendly, ‘self-promotion’ which could be used to be seen as competent, ‘exemplification’ which could be used to be seen as dedicated and hardworking, ‘intimidation’ which could be used to be seen as threatening, and ‘supplication’ which could be used to be seen as needy. Impression management can also be understood as either tactical (short term) or strategic (long term) and assertive (initiated by the actor) or defensive (used by the actor for responding to an undesired image) (Tedeschi & Melburg, 1984). An interesting research finding in the field of impression management in the recent times is that impression management strategies used by women differ from that of men (Guadagno & Cialdini, 2007).

However, studies also point at the scarcity of research on impression management strategies used by women, especially in the Indian context. There have been some research contributions in this field from Asian countries such as Hong Kong, China and Singapore, but India is yet to be churned adequately for insights in this field (Barkema et al., 2015).

ATGS and FIMWI

In the Indian context, FIMWI was proposed (Sanaria, 2016). This framework explored the impression management techniques used by women in India. It used the social role theory (Guadagno & Cialdini, 2007), masculine and feminine job roles and ATGS to understand the types of impression management strategies used by women in India.

ATGS (Larwood, 1991) was expected to affect the choice of impression management behaviours adopted by women in India. Women would have either an accepting or challenging ATGS. This variation in ATGS could provide a rich ground to explain the process underlying the choice of impression management strategies by women in Indian organisations (Sanaria, 2016).

Gender Role Theory

Gender role theory (Sczesny et al., 2018) describes behavioural norms for women and men indicating that the expected behaviours are different for men and women. According to these norms, women are expected to engage in more communal behaviours, whereas men are expected to engage in more agentic behaviours (Smith et al., 2013). Drawing implications from the above, actions that demonstrate modesty, friendliness, submissiveness, unselfishness and concern for others are stereotyped as feminine tactics. Juxtaposed to this, behaviours that demonstrate self-confidence, assertiveness, self-reliance, directness and instrumentality represent the masculine stereotype (Bolino et al., 2016).

Gender Stereotypes and ATGS

Gender stereotypes have been extensively researched (Ellemers, 2018). The concept of ATGS was introduced by Sanaria (2016). Attitudes being a strong indicator of behaviour makes the concept of ATGS a predictor of the way one would behave/respond towards a particular gender stereotype. In some situations, people prefer preserving the gender stereotype. This is defined as ‘accepting ATGS’. Similarly in some situations, people do not accept the stereotype and challenge it. This is defined as ‘challenging ATGS’. These are the two types of ATGS found in Indian context (Basu, 2008).

ATGS and Impression Management Behaviours

Reconceptualising ATGS

ATGS could have a high and a low level. These high or low levels of attitudes are described as follows:

High Accepting ATGS. The person having accepting attitude at high levels would tend to accept the stereotypes of the gender they identify as. For example, a woman would readily accept the identity of being soft, subtle and communal as per the common stereotypes held about women by the society.

Low Accepting ATGS. The person having accepting attitude at low levels would tend to be less accepting of the stereotypes of the gender they identify as. For example, a woman would rarely accept the stereotype of being soft, subtle and communal.

High Challenging ATGS. The person having challenging attitude at high levels would tend to challenge the stereotypes of the gender they identify as. In this scenario, a woman would strongly deny the stereotypes held about women being soft, subtle and communal. She would consider women as capable as men in any front.

Low Challenging ATGS. The person having challenging attitude at low levels would tend to be less challenging of the stereotypes of the gender they identify as. For example, a woman would rarely challenge the stereotypes held against her about being soft, communal and submissive.

The two dimensions, accepting and challenging ATGS, are independent of each other (Larwood, 1991). If we juxtapose the two dimensions (high and low) of the two types of ATGS, we get four combinations as exhibited in Table 1.

Table 1. Types of ATGS.

Source: The authors.

Types of ATGS

This section describes each type of ATGS that has been derived from the combination of ‘high’ and ‘low’ levels with ‘accepting’ and ‘challenging’ ATGS. These are based on the descriptions of internalisation and compliance (Kelman, 1958). The high levels of accepting or challenging ATGS could be associated with internalisation since the acceptance of the gender stereotype or the challenge against the gender stereotype is congruent and integrated with their value system which either accepts women as communal or identifies them as agentic like men. The low levels of accepting or challenging ATGS could be associated with compliance since the acceptance of the gender stereotype or the challenge against the gender stereotype is caused not because of one’s belief in the content of the stereotypes. It is accepted or challenged only in situations in which the individual hopes to gain rewards or avoid punishment (Kelman, 1958).

High Accepting, High Challenging (HAHC). Women with an attitude that is highly challenging yet highly accepting of the gender stereotype would tend to oscillate between being the quintessential feminine to the ultra-masculine. She would tend to accept stereotypes but also challenge them. She would believe in the ability to ace her performance in all jobs, even in those that are typically assumed to be masculine in nature. In situations where she is required to be soft and communal, she would present herself as optimally soft and communal. In situations that require her to be dominant and agentic, she would ace in displaying those attributes as well. It could be said that she would find a need to be high on both the accepting and challenging attitude towards the gender stereotypes for she would neither want to lose her prowess nor the comforting softness that she is a possessor of. Maintaining both these aspects are extremely important for her. The combination of high accepting and high challenging ATGS indicates the strong presence of internalisation of beliefs that women can be both agentic and communal as per situational needs.

Low Accepting, High Challenging (LAHC). Women with an attitude that is low accepting and high challenging of gender stereotypes will tend to not accept or challenge the stereotypes. She will tend to challenge the stereotypes because it is congruent with her value system that considers women capable of being agentic unlike the stereotype that labels them as communal. However, she will tend to accept the gender stereotypes only when she feels that complying with it would lead her to specific rewards and help her avoid punishments.

High Accepting, Low Challenging (HALC). Women with an attitude that is highly accepting, and low challenging of the gender stereotype, will tend to accept and be less challenging of the stereotype about women. The combination of high level of accepting attitude and low level of challenging attitude could also be explained with the help of internalisation and compliance (Kelman, 1958). In this situation, the woman will tend to accept the way the society identifies her as a soft communal entity. She will thus find it important to preserve the stereotype because it is congruent with her existing belief system that considers woman as friendly, submissive and communal. In other words, she will have internalised the stereotype which will induce her to accept it. However, she may challenge the stereotype about women only when she wants to gain specific rewards (for example, support of popular radical feminists) or wants to avoid punishment (for example, fear of social isolation by peers who are radical feminists).

Low Accepting, Low Challenging (LALC). Women with an attitude that is low accepting and low challenging of the gender stereotype would tend to be less accepting and less challenging of stereotypes about women. Accounting for the low accepting attitude in the combination, the woman would consider women as soft and communal only to gain a specific reward or avoid a negative consequence. However, she will challenge the gender stereotype not because of her existing beliefs but because through her challenging of the stereotypes too, she aims to gain rewards and avoid punishment. The combination of low accepting and low challenging ATGS indicates the strong presence of compliance in women who have this combination of ATGS.

Social Identity Theory

We use the social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1979) to further understand how ATGS impacts the choice of impression management strategies. The social identity theory is a social psychological theory of intergroup relations, group processes and the social self. According to the social identity theory, we categorise the social world as in-groups and out-groups. An in-group is a social category or group with which we identify strongly. An out-group, conversely, is a social category or group with which we do not identify. Simply put, the social identity theory helps us put people into buckets of ‘us’ and ‘them’ (Tajfel & Turner, 1979).

In a collectivistic country such as India, in-group members are perceived from the focal point of the ‘relational self’. It means that when we interact with in-group members, our self-knowledge is largely derived from our knowledge about our significant others, and the significant others play a major role in characterising ourselves (Chen et al., 2011). We approach them using familial terms and treat them as our kins. On the contrary, we perceive our out-group members from the focal point of ‘individual self’. The ‘individual self’ focusses on one’s unique side. It is a combination of attributes like one’s traits, goals and aspirations, experiences, interest and behaviours that differentiate the person from others. This representation of the self is relatively independent of relational bonds or memberships in-groups. These two versions of self or two different identities of a person generate differences in our ways of perceiving people (Sedikides et al., 2011). As individuals interact with each other and become engaged with these groups, their identities become more prominent. Social categories such as race, ethnicity and gender are most salient. These serve to create and perpetuate in-groups and out-groups in societies and organisational settings. Therefore, socially constructed identities based on group membership can be a source of misunderstanding, conflict and problems (Haynes & Ghosh, 2012).

In the context of understanding gender stereotypes and the way in which these stereotypes influence decision-making (choice of impression management in this context), social identity theory plays an intriguing role. It helps us understand why human beings, who are supposed to be rational creatures, or at least capable of rational thought and behaviour continue to operate according to gender expectations and stereotypes. Similarly, it can also help us ponder over the reasons owing to which they challenge a gender stereotype. Identity theory supports understanding the reasons for which such gender stereotype preserving or challenging behaviours are displayed (Carter, 2014). Hence, this theory will be used to find the cause due to which a specific ATGS influences the choice of impression management techniques.

How Does ATGS Influence Impression Management Behaviours?

Attitudes have an affective, cognitive and behavioural dimensions. Therefore, attitudes contribute extensively to the development of thoughts, feelings and behaviour. Due to this three-dimensional impact, almost every domain of our life, lies within the panorama of attitudes (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1977). This implies that decision-making in each of domains is influenced by our attitudes. This further implies that decision-making or the choices that one makes in one’s workplace is also influenced by attitudes.

As understood from the review of past literature, stereotypes hint towards a perception that has been formed towards a phenomenon over a large time duration by a large group of people. Since these perceptions have been historically preserved and reinforced time and again, they root themselves in the collective consciousness. This process offers stereotypes a kind of omnipotence that makes it difficult for people to be blind to it. It also implies that stereotypes are an integral part of the society and makes its presence felt in every part of it (Ellemers, 2018). The Indian workplace is still struggling to inculcate gender egalitarianism in its culture. Exploring the impact of ATGS in impression management behaviours adopted by women in organisations is, therefore, a relevant field of inquiry in the organisations (Sanaria, 2016).

From the lens of organisational dramaturgy that was conceptualised by Erving Goffman (2010), every individual in the workplace could be perceived as an actor. This actor has a target audience and wishes to influence them by creating, preserving and protecting an alter image of themselves. In other words, every actor engages in the process of impression management in order to create a favourable image in the minds of their target audience (Gardner III, 1992). Therefore, it could be said that the choice of impression management techniques used by the various actors in organisations would be affected by their ATGS.

Taking the categorisation of in-group and out-group and the relational and individual identities in consideration, we attempt to explore the impact of ATGS in the choice of impression management tactics by women working in Indian organisations.

High Accepting, High Challenging (HAHC). As discussed earlier, these women accept and reject the gender stereotypes. Taking insights from the social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1979), identification with in-group members transforms self-conception and behaviour to embody the group attributes which is manifested through attitudes and behaviours sanctioned by the group. These attitudes and behaviours are internalised as an evaluative self-definition that governs what one feels, thinks and does (Hogg et al., 2012). We, therefore, propose that women with this combination of ATGS will have an accepting ATGS while interacting with their in-group members since the stereotypes held by the in-groups have been internalised.

However, while interacting with the out-group members, she will display a challenging ATGS. According to the social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1979), it is established that the purpose of group norm or group prototype is to maximise the contrasts between in-groups and out-groups. This implies that adhering to the group norm or embodying the group prototype requires one to distance oneself from the group norms or prototype of the out-groups (Hogg et al., 2012). One way through which the distance or contrast between the in-groups and the out-groups could be created is by challenging the stereotypes held by members of the out-group. This could be a reason due to which she would tend to challenge stereotypes held by out-group members.

Therefore, her choice of impression management tactics will be aimed at preserving stereotypes in her interaction with in-group members. It will be aimed at challenging the stereotypes in her interactions with out-group members.

High Accepting, Low Challenging (HALC). Women having this combination of ATGS would be highly accepting and are less likely to challenge the stereotype. We discuss this combination of ATGS using the concepts of personal identity and social identity from the social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1979). Social identity refers to people’s self-categorisations in relation to their group memberships. Personal identity refers to the unique ways that people define themselves as individuals (Leaper, 2011). For women having a combination of high accepting and low challenging ATGS, it could be said that their social identity is stronger than their personal identity. Their identity emanates from the definition of themselves that they gather from their social surroundings. It is their strong social identity that accounts for their high accepting ATGS. Since the stereotypes about women prevalent in the society has been internalised owing to its congruence with the value system (Kelman, 1958), the woman will have an accepting ATGS for both in-groups and out-groups.

She would challenge the stereotype only in scenarios where challenging the stereotype would provide her with some benefit or save her from punishment. In other words, challenging the stereotype would be a result of compliance with the situation (Kelman, 1958).

Low Accepting, High Challenging (LAHC). Women having this combination of ATGS tend to challenge the stereotypes about women and are less likely to accept it. From the social identity theory perspective, it could be said that for women with such a combination of ATGS, personal identity overpowers the social identity. Their definition of self is defined entirely by themselves. The societal description of women are redundant for them. Therefore, the prevailing stereotypes of friendly, submissive and communal for a woman would be challenged by them. Thus, their choice of impression management techniques would be aimed at challenging the stereotypes about women. Since they have internalised the beliefs that women can be agentic and authoritative and are not restricted to being communal and submissive, they will challenge the gender stereotype with both in-groups and out-groups.

One of the reasons why they would accept the stereotypes would be the possibility of gaining a reward or avoiding a punishment. We could therefore say that accepting the stereotypes in the case of women having high challenging and low accepting ATGS would be a product of compliance to the situation (Kelman, 1958).

Low Accepting, Low Challenging (LALC). Women with this combination of ATGS, tend to neither accept nor challenge the gender stereotype. From the social identity theory perspective, it could be said that they place value on both personal and social identity. However, they subscribe to the personal or social identities based on the possibility of gaining a reward or avoiding a punishment. Driven by their compliance with situations, they may either challenge the gender stereotypes or may accept the gender stereotypes. We argue that if they find subscribing to their personal identities more rewarding than subscribing to their social identity, they exhibit low acceptance towards gender stereotypes.

However, it could be possible that if their fear of rejection by society is due to their challenging of the gender stereotypes, this may contribute to the presence of a more conforming nature. This could account for their low challenging ATGS. Therefore, their impression management technique would aim at conforming with the social norms due to their low accepting and low challenging ATGS with both in-groups and out-groups.

Choice of Impression Management Tactics Basis ATGS

It was proposed with the help of social identity theory that ATGS influences the choice of impression management tactics used by women in workplaces, we now suggest which impression management tactics would be preferred by women given a particular combination of ATGS.

High Accepting, High Challenging (HAHC)

As discussed above, women with this combination of ATGS will aim to preserve the stereotypes while interacting with in-groups and will challenge the stereotypes while interacting with out-groups. She will thus make use of soft impression management techniques in order to preserve the stereotype (Sanaria, 2016). Techniques such as ingratiation and coalition are soft management techniques which would be used with in-group members. The rationale behind the usage of techniques such as ingratiation and coalition would be the exhibition of the communal, submissive and friendly attributes that are central to the gender stereotype help about women (Sanaria, 2016). Women are perceived as more effective when displaying behaviours which are considered appropriate based on gender stereotypes (Carli, 1990). However, in order to maintain the contrast between herself and the members of the out-group, she will try to present herself as antithetical to the gender stereotypes by challenging them. A woman with challenging ATGS will tend to display hard impression management strategies (Larwood, 1991; Rudman, 1998; Rudman & Glick, 2001). In order to present herself as agentic and authoritative as men, she will make use of hard impression management techniques such as intimidation and blocking with out-groups members.

Ingratiation. One of the techniques used by in-group members is ingratiation. It is a technique whereby individuals seek to be viewed as likable by flattering others or doing favours for them (Bolino & Turnley, 2003). Using this technique, they will try to present themselves in a more favourable light to their in-group members. They may engage in acts of praising and flattering to make themselves more likeable. This way, the tactic of ingratiation will help them preserve the stereotype as guided by their accepting ATGS.

Coalition. Another tactic of impression management that could be proposed in the context of in-groups is coalition. Coalition tactic is used to mobilise support from allies (Vanhaltren & Peter, 2019). It could be used to form networks of people to gather their support and validation for achieving a common goal. Propelled by their accepting ATGS, it could be said that they would work towards forming close-knit circles of their in-group members to draw more support from them. Exemplification could be also used as an impression management technique for in-group members.

Intimidation. One of the techniques used with out-group members is intimidation technique. It is a technique (Bolino & Turnley, 2003) whereby individuals seek to be viewed as intimidating by threatening or bullying others. In order to challenge the gender stereotype women could engage in acts like calling by the name, providing radical criticism, directing and giving instructions and the like while interacting with people from the out-group.

Blocking. Another technique that could be used with out-group members is blocking. It deals with the usage of threats to notify outside agencies, engaging in work slowdowns and reduction of pro-social behaviour (Kipnis et al., 1980). Verbal blocks could be used to halt an ongoing interaction and put one’s professional identity to the forefront of the interaction and thus establish her presence (Hatmaker, 2013). Through these practises, the stereotypes about women held by the out-group members would be challenged.

Assertiveness and self-promotion could also be used as impression management techniques for out-group members.

Low Accepting, High Challenging (LAHC)

As proposed earlier, this combination of ATGS will induce women to use hard management techniques since this would challenge the stereotype for both out-group and in-group members. Hard impression management strategies use a combination of direct and aggressive impression management strategies such as assertiveness, self-promotion, intimidation and the like (Sanaria, 2016).

Assertiveness. It is defined as demanding forcefully and persistently by establishing one’s ideas, feelings (Vanhaltren & Peter 2019). This challenges the common stereotype of women being communal and submissive.

Self-promotion. It occurs when an individual tries to associate themselves with someone or something that is viewed positively by their target audience. People practising self-promotion try self-enhancements, entitlements and basking in reflected glory (Gardner III, 1992). This challenges the common stereotype of women being modest and unselfish.

Intimidation and blocking techniques could also be used in this context.

High Accepting, Low Challenging (HALC)

As proposed earlier, this combination of ATGS will induce women to use soft management techniques with both in-groups and out-groups since they would accept the stereotype on most occasions and want to preserve these stereotypes. Soft impression management strategies include indirect and subtle impression management strategies such as ingratiation, coalition, exemplification and the like (Sanaria, 2016).

Exemplification. It is a process by which individuals seek to be viewed as dedicated by going beyond the call of duty (Bolino & Turnley, 2003). It is used to present oneself in an honest and straightforward way by showing integrity and exemplary behaviour (Gardner III, 1992). This behaviour would largely be driven by the need to be consistent with the stereotypes held about women being communal. Ingratiation and coalition techniques can also be used in this context.

Low Accepting, Low Challenging (LALC)

As proposed earlier, women with this combination of ATGS, have a low acceptance for gender stereotypes yet tend not to challenge the same, possibly to gain rewards or avoid punishments. The resultant attitude is a conforming one that aims to preserve gender stereotype without accepting it. In the context of conforming to the stereotypes, the following impression management techniques may be used.

Supplication. Supplication makes use of passive behaviours, such as acting needy to gain assistance or sympathy, or pretending to not understand a task to avoid an unpleasant assignment (Bolino & Turnley, 1999). Through the technique of supplication, one aims at presenting their weaknesses and broadcasting one’s limitations. It could be appropriately used in an LALC combination since the appearance of weak and needy could be leveraged in a situation where a gender ideal behaviour (stereotype) is expected from the woman and her low accepting ATGS directs her to refrain from doing it.

Face Saving Techniques. Face saving techniques like defence of innocence would be used in crisis situations where, the low accepting ATGS would have directed one to transgress the expected gender behaviours. In this very scenario, their low challenging ATGS would help the person to dissociate herself from an alleged event and hence prove that she was innocent and did not challenge the stereotype (Gardner III, 1992).

‘Apology’ could be another face-saving technique in the context of crisis situations. Through apology, the woman could convince her target audience that the situation is not an appropriate description of what she is. This is another possible way through which she would manifest her low accepting ATGS along with the low challenging ATGS (Gardner III, 1992).

A summary of the impression management techniques used by women with different combinations of ATGS can be seen in Table 2.

Table 2. Summary of Impression Management Techniques Used by Women with Different Combinations of ATGS.

Source: The authors.

Theoretical, Practical Implications and Future Research Possibilities

This article holds relevance due to the following reasons. First, there is a dearth of studies focusing on impression management strategies used by women in the Indian context (Sanaria, 2016). This article contributes to the research on impression management strategies used by women by building upon their ATGS. Second, this article, in its endeavour to explore ATGS, tries to look at various combination of ATGS using the high/low dimension and the accepting/challenging dimension. This highlights that it would be unfair to presume that ATGS could either be accepting or challenging. This study contributes towards the understanding that it should be witnessed under the lens of one’s understanding of oneself and the situation in which they perform as actors. Third, impression management is said to be the result of a multiplicity of factors, many of which are yet to be unearthed by existing research. This article contributes by identifying the type of ATGS, the nature of one’s identity using the social identity theory as relevant factors for determining the choice of impression managements.

An interesting finding in prior research is that observers tend to react more favourably to attempts at impression management that fit gender role prescriptions (Rudman, 1998; Smith et al., 2013). It could thus be said that using the same impression management tactic may lead to different outcomes for men and women. It was found that men who used intimidation received more favourable evaluations, as compared to women. In addition to the same, the use of intimidation did not make men less likeable, but it affected the likeability of women negatively (Bolino & Turnley, 2003). On the contrary, Kipnis and Schmidt (1988) found that ingratiation led to positive evaluations for women, but it did not work the same way for men. This, thus, reflects the success of soft impression management techniques in the context of women. Therefore, exploring the impact of ATGS on impression management ATGS, specifically those with challenging ATGS, can potentially contribute towards novel findings in the field of impression management strategies by women.

Women in workplaces are usually perceived as emotional, illogical and intuitive decision-makers (Green & Casell, 1996). Along with the same, there is also a common perception that they are physically, mentally and emotionally less capable in confronting certain challenges because of being temperamental and lacking in motivation (Tabassum & Nayak, 2021). These stereotypes about women in workplaces that have been a part of the organisational narrative take into consideration the opinions of the larger society that contributes to the formation of these stereotypes about women. Our study allows a window to verify if these stereotypes still hold true and, if it does, do women accept it or challenge it.

Conclusion

The article aims to initiate steps towards recognising the efforts of women to sustain in organisational climate that favours masculinity. The Indian culture is marked by an unequal societal status of women and men, and this inequality plays out in all walks of life. Workplaces are no exception. This societal placement has been the forerunner to a desperation for equality, which has given rise to several women’s movements. This body of work, thus, brings to forefront an interface between gender and ATGS and encourages dialogues on the employee–employer relationship, the Indian organisational culture and more importantly the challenges faced by women employees in the organisations. The discussion addresses the lack of research on the idiosyncrasies of Indian workplaces in the sphere of impression management and explains the context that drives women to use them. While explaining the numerous aspects that women keep in mind while deciding upon their impression management techniques, the article emphasises on the intersection of social forces that are at play (like their personal vs social identity and their in-groups and out-groups) in the Indian woman’s workplace and the resilience and cognitive pro-activeness required to address them. Some future directions for research in this context could commence in the lines of gathering narratives on gender stereotypes in workplace to understand if perceptions about women have changed or are still the same, comparing intergenerational perspectives on impression management by women in workplace and the like. We hope that this article encourages future research on the aspects related to ATGS and impression management behaviours to promote the voice and discuss the challenges faced by women employees in Indian organisations.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1977). Attitude-behavior relations: A theoretical analysis and review of empirical research. Psychological Bulletin, 84(5), 888.

Barkema, H. G., Chen, X.-P., George, G., Luo, Y., & Tsui, A. S. (2015). West meets east: New concepts and theories. Academy of Management Journal, 58(2), 460–479.

Basu, S. (2008). Gender stereotypes in corporate India: A glimpse. SAGE Publishing.

Bolino, M. C., & Turnley, W. H. (1999). Measuring impression management in organizations: A scale development based on the Jones and Pittman taxonomy. Organizational Research Methods, 2(2), 187–206.

Bolino, M. C., & Turnley, W. H. (2003). More than one way to make an impression: Exploring profiles of impression management. Journal of Management, 29(2), 141–160.

Bolino, M., Long, D., & Turnley, W. (2016). Impression management in organizations: Critical questions, answers, and areas for future research. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 3(1), 377–406.

Carli, L. L. (1990). Gender, language, and influence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(3), 941–951.

Carter, M. J. (2014). Gender socialization and identity theory. Social Sciences, 3(2), 242–263.

Chen, S., Boucher, H., & Kraus, M. W. (2011). The relational self. In S. J. Schwartz, K. Luyckx, & V. L. Vignoles (Eds.), Handbook of identity theory and research (pp. 149–175). Springer Science + Business Media.

Eagly, A. H., & Sczesny, S. (2019). Gender roles in the future? Theoretical foundations and future research directions. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1965.

Ellemers, N. (2018). Gender stereotypes. Annual Review of Psychology, 69, 275–298.

Gardner III, W. L. (1992). Lessons in organizational dramaturgy: The art of impression management. Organizational Dynamics, 21(1), 33–46.

Goffman, E. (2002). The presentation of self in everyday life. Anchor.

Goffman, E. (2010). The presentation of self in everyday life: Selections. In The production of reality: Essays and readings on social interaction (p. 262).

Green, E., & Casell, C. (1996). Women managers gendered cultural processes and organisational change. Gender, Work and Organization, 3(3), 168–178.

Guadagno, R. E., & Cialdini, R. B. (2007). Gender differences in impression management in organizations: A qualitative review. Sex Roles, 56(7–8), 483–494.

Hatmaker, D. M. (2013). Engineering identity: Gender and professional identity negotiation among women engineers. Gender, Work & Organization, 20(4), 382–396.

Haynes, R. K., & Ghosh, R. (2012). Towards mentoring the Indian organizational woman: Propositions, considerations, and first steps. Journal of World Business, 47(2), 186–193.

Hogg, M. A., van Knippenberg, D., & Rast III, D. E. (2012). The social identity theory of leadership: Theoretical origins, research findings, and conceptual developments. European Review of Social Psychology, 23(1), 258–304.

Jones, E. E., & Pittman, T. S. (1982). Toward a general theory of strategic self-presentation. In J. Suls (Ed.), Psychological perspectives on the self (Vol. 1, pp. 231–262). Erlbaum.

Kelman, H. C. (1958). Compliance, identification, and internalization three processes of attitude change. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 2(1), 51–60.

Kipnis, D., Schmidt, S. M., & Wilkinson, I. (1980). Intraorganizational influence tactics: Explorations in getting one’s way. Journal of Applied Psychology, 65(4), 440–452.

Kipnis, D., & Schmidt, S. M. (1988). Upward-influence styles: relationship with performance evaluations, salary, and stress. Administrative Science Quarterly, 33(4), 528–542.

Larwood, L. (1991). Start with a rational group of people…: Gender effects of impression management in organizations. In R. A. Giacalone & P. Rosenfeld (Eds.), Applied impression management: How image-making affects managerial decisions (pp. 177–194). SAGE Publishing.

Leaper, C. (2011). More similarities than differences in contemporary theories of social development? A plea for theory bridging. Advances in Child Development and Behavior, 40, 337–378.

Rudman, L. A. (1998). Self-promotion as a risk factor for women: The costs and benefits of counterstereotypical impression management. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(3), 629–645.

Rudman, L. A., & Glick, P. (2001). Prescriptive gender stereotypes and backlash toward agentic women. Journal of Social Issues, 57(4), 743–762.

Sanaria, A. D. (2016). A conceptual framework for understanding the impression management strategies used by women in Indian organizations. South Asian Journal of Human Resources Management, 3(1), 25–39.

Sczesny, S., Nater, C., & Eagly, A. H. (2018). Agency and communion: Their implications for gender stereotypes and gender identities. In A. Abele & B. Wojciszke (Eds.), Agency and communion in social psychology (pp. 103–116). Routledge.

Sedikides, C., Gaertner, L., & O’Mara, E. M. (2011). Individual self, relational self, collective self: Hierarchical ordering of the tripartite self. Psychological Studies, 56(1), 98–107.

Smith, A. N., Watkins, M. B., Burke, M. J., Christian, M. S., Smith, C. E., Hall, A., & Simms, S. (2013). Gendered influence: A gender role perspective on the use and effectiveness of influence tactics. Journal of Management, 39(5), 1156–1183.

Tabassum, N., & Nayak, B. S. (2021). Gender stereotypes and their impact on women’s career progressions from a managerial perspective. IIM Kozhikode Society & Management Review, 10(2), 192–208.

Tajfel, H., Turner, J. C., Austin, W. G., & Worchel, S. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. Organizational Identity: A Reader, 56(65), 9780203505984-16.

Tedeschi, J. T., & Melburg, V. (1984). Impression management and influence in the organization. In S. B. Bacharach & E. J. Lawler (Eds.), Research in the Sociology of Organizations (pp. 31–58). JAI.

Vanhaltren, C. J., & Peter, A. J. (2019). A conceptual framework on constructs of impression management: A review study with special reference to academicians. Think India Journal, 22(10), 6357–6361.