1Indian Institute of Management, Bangalore, Karnataka, India

2MICA, Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India

3Ganpat University, Kherva, Gujarat, India

Creative Commons Non Commercial CC BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License (http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-Commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed.

Video ads that tell stories have become a popular method of connecting with viewers and making them feel emotionally invested in a product or a service. Long-form videos, as opposed to shorter types of advertising like TV spots and print advertising, can persuade viewers with a sincere and compelling brand story, creating favourable brand associations. We empirically investigated the impacts of narrative transportation caused through audio-visual storytelling advertising on consumers’ affective, sensory, cognitive, behavioural experiences and brand equity states using structural equation modelling in SPSS Amos 25.0. Our research supports the relationship between ad-elicited narrative transportation and various brand effects. We also evaluated the moderating effect of previous negative online purchase experiences (POPE) on all forms of advertising experience. The impact of high-quality competing advertising on the impressions formed by consumers who have had negative prior experiences and the strategies employed by brands to use negative experiences build positive equity for their brands. Discussions and implications are discussed.

Customer experience, brand equity, storytelling advertising, prior customer experiences, brand perception

Introduction

Video advertising is projected to increase from $35.45 billion to $69.43 billion by 2024 (Nilsen, 2022). Video commercials are effective, according to 64% of 25 to 34-year-old and 70% of 16 to 24-year-old who have seen social media clips recently. Since 1998, narrative-style video storytelling advertising has gained popularity. Advertisers can use drama, slice-of-life and transformative advertising as formats to communicate a brand story (Polletta & Callahan, 2017). This advertising style tends to appeal to consumers’ emotions, especially when drawn into the storylines to facilitate changes in the customer experience, promoting brand awareness and overall strong brand equity. Unlike traditional or print advertisements, video storytelling advertising uses TV, desktop, laptop and mobile platforms (Nilsen, 2022).

Academics have used narrative advertising methods to understand video storytelling advertising due to its growing prominence in digital advertising (Woodside et al., 2008). According to Chen (2013), through this study, we employ video storytelling advertising to link ‘companies in an ad story and self-related goals’ and to convey ‘the fundamental message by telling a story’ (Escalas, 2003, p. 168). Customers feel more connected to a company when it has a story, which boosts engagement (Kang et al., 2006). As they explain concepts through stories, brand story advertisements are believable due to their accuracy and narrative structure (Kang et al., 2006; Lee et al., 2017).

According to studies, narrative advertising may be more persuasive. Previous studies examined how customers receive data on product attributes and video storytelling components (like music, humour or spokespersons). The length, flow, frequency and relevancy predict retention of the message in video storytelling advertising. Brechman and Purvis (2015) studied the possibility of brand narratives affecting consumer perceptions in a made-up universe. According to their research, customer receptivity determines how impactful story advertising is.

Story advertising has consistent, non-product-specific effects (Kang et al., 2020) and studies on search and experience goods, premium scent items (Ryu et al., 2018), food service and restaurants and financial and investment services revealed positive narrative impacts (Godey et al., 2016). However, most studies have used student samples comprising undergrads and graduates (Lien & Chen, 2013; Mazzocco et al., 2010). Despite being related to the product categories examined, customer types are yet to be investigated.

Many advertising studies have focused on deconstructing narrative print ads to examine their influence on advertising-related characteristics (An et al., 2020). According to Chen (2015), oral narrative advertising can influence consumer attitudes and product evaluation. Modern advertising relies more on video than print, particularly in digital media, which may have reduced the managerial relevance of print-only studies (Berezkin, 2013). Few studies have examined how narrative advertising can help brands and consumers form personal connections by conjuring up pleasant brand experiences (da Silva & Larentis; Hagarty & Clark, 2009). Limited research has been conducted to determine whether video advertising can affect consumer experience and brand equity.

This study asks, ‘Does video story advertising increase customers’ affective, behavioural, sensory and intellectual experiences, which in turn impact overall brand equity, consisting of perceived worth, awareness and loyalty with brands’? In order to better comprehend these factors in narrative advertising research and conduct a more extensive analysis of the phenomenon of video storytelling advertising, we propose merging narrative mobility and marketing impact variables (Keller, 2020).

Literature Review

Advertising, Narrative Transportation and Persuasion Effects of Video Storytelling

Video storytelling advertising would define brand meanings using a compelling story and brand benefits that are personally relevant to the viewer (Haring, 2003). ‘All mental processes and capacities converge on narrative events’ is the definition of storytelling (Green & Brock, 2000, p. 701). We postulate that viewers become entirely engrossed in a brand’s video storytelling initiative and feel like the characters featured in the advertisement (Curenton et al., 2008). A reduced desire to concentrate on an advertisement’s advantages promotes peripheral processing (Brechman & Purvis, 2015). A compelling video narrative ad could promote heuristic processing, decrease elaboration and boost persuasion (Bordahl, 2003; Lim & Childs, 2020). Emotionally invested customers are far less inclined to resist persuasion and develop counterpoints to restrict the efficacy of advertising (Iurgel, 2003; Koenig & Zorn, 2002).

The majority of research on narrative advertising has concentrated on conventional advertising factors such as improved brand recall (Brechman & Purvis, 2015), mindset toward the promoted product (Wang & Calder, 2006b), the promoted brand, as well as the willingness to buy or use it (Sangalang et al., 2013). A more fundamental question remains unanswered, forming the basis of many advertising studies: How can compelling advertising contribute to the generation of favourable branding outcomes that result in long-term gain, as several marketing professionals and business experts anticipate? By telling a compelling tale, brand storytelling advertising can strengthen a brand and impact the advertising experience of customers and other brand-related outcomes (Sangalang et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2015).

Advertising Experience

Advertising experience is a subjective consumer response that can be elicited by a narrative brand message (Hung et al., 2012). Brand tales are an example of a ‘managed advertising effort’ that can enhance the advertising customer journey and impact the results, increasing brand equity and improving brand perception, among other things (McEwen et al., 2016). This complex marketing term has been used to examine the impact of advertising experience on outcomes like trust, brand loyalty, recommendation, preference, uniqueness and fulfilment (Betty, 2020; Xu et al., 2017). In video narrative advertising, affective advertising brand experience relates to feelings, emotional states and feelings, whereas sensory advertising brand experience refers to how consumers respond to colours, sounds, sights and phrases (Papacharissi & Oliveira, 2012; Ramon, 2021; Urgesi et al., 2016). While behavioural advertising brand experience encompasses customers’ physiological experiences, bodily acts and purchasing and consumption behaviours, the intellectual advertising brand journey corresponds to conflict-solving skills, stimulated thinking and company interest (Barcelos & Gubrium, 2018). We suggest examining how brand stories affect the kind of experience, that is, how storytelling advertisements alter behavioural, intellectual, sensory and emotive ad experiences. Thus, we predict:

H1: Storytelling ads have a significant influence on advertising behavioural experience.

H2: Storytelling ads have a significant influence on advertising intellectual experience.

H3: Storytelling ads have a significant influence on advertising sensory experience.

H4: Storytelling ads have a significant influence on advertising affective experience.

Advertising Brand Experience and Brand Equity

Experiences can be categorised according to philosophers, cognitive scientists and management specialists. Our hypothesis states that brand-related stimuli, such as shades, forms, fonts, layouts, slogans, mascots and brand personalities, evoke experiential qualities (Koll et al., 2010; Machado et al., 2019; Rossolatos, 2020). A single stimulus triggers no one experience dimension. Colour schemes, textures, fonts and designs can elicit sensory, emotional or intellectual responses (such as the blue bird for Twitter) or both (e.g., when intricate patterns are used in designs; Suarezserna, 2020). Taglines, logos and brand figures can inspire creative feelings, thoughts or actions (Hepola et al., 2017). For instance, ‘Amul Girl’ relates directly to the advertising mascot of the Indian dairy company Amul. Any positive brand encounters that consumers have should leave a lasting impression, where a permanent trace is preserved in the consumer’s long-term memory based on several brand-related stimuli (Yoo, 2008). We investigate if the notion of advertising brand experience encountered here is in line with consumers’ past experiences and how it impacts brand equity.

An asset or liability linked to a brand, its name, and its symbol adds or subtracts value provided to a firm or its customers (Seifert & Chattaraman, 2020). Brand equity is the added value a product receives from its brand name (Koll et al., 2010). Suarezserna (2020) defined brand equity as the value a brand receives due to its strong relationship with potential customers and key stakeholders.

Brand advertising seeks to raise awareness and subsequently influence a consumer’s purchase decision (Machado et al., 2019). Consumers make decisions based on prior knowledge (Machado et al., 2019), so brand awareness remains critical (Godey et al., 2016). In this case, storytelling helps consumers remember information, increasing awareness and recall. Hung et al. (2012) found that sellers use stories to engage, persuade and educate consumers. Thus, we predict:

H5: Advertising behavioural experience has a significant influence on overall brand equity.

The buyer’s perception of a product or service’s quality is critical in marketing. A higher perceived worth leverages or gives an advantage to brands to charge higher prices (Godey et al., 2016). According to Lee and Jahng (2020), stories impact brand experience, which impacts the perceived worth of the brand in consumers’’ minds. Storytelling as a marketing strategy builds trust because it’s less intrusive than traditional marketing campaigns (Grigsby & Mellema, 2020). Similar to Lundqvist et al. (2013), the story influences how consumers associate the product and brand. Brand associations influence consumption and perceived brand associations are essential to brand equity (Chen et al., 2012). To build a strong brand, the consumer must have a positive association with it, which increases the product’s value (Chen, 2015). The story serves both as an information source and a way to get consumer equity. Thus, we predict:

H6: Advertising intellectual experience has a significant influence on overall brand equity.

H7: Advertising sensory experience has a significant influence on overall brand equity.

A loyal consumer increases purchases and helps gain overall brand trust, increasing the company’s value (Aaker et al., 2012). According to Fog et al. (2005), consumers are loyal to a brand because they perceive value in the product or service. He further argues that using storytelling to connect with consumers will lead to more loyal customers. According to Lundqvist et al. (2013), consumers who felt emotionally connected to a brand were more likely to be loyal to it, which is reflected in two ways: repeat purchases or brand equity (Ohanian, 1990). According to Lee et al. (2005), a company must create a bond between the brand and the consumer. Thus, we predict:

H8: Advertising affective experience has a significant influence on overall brand equity.

Moderating Effect of Negative Prior Online Purchase Experience

According to Helson (1964), the sum of an individual’s experiences, context or background, and stimuli determines how they respond to an evaluative task. Online shopping is increasing day by day (Nilsen, 2022), so they tend to view it as more precarious than traditional in-store transactions (Armstrong & Overton, 1977; Sawhney et al., 2005). So, the quality of the experience is crucial for online shoppers, and it can only be achieved from previous purchases (Bhattacharya et al., 1995). Our past experiences will heavily influence our actions in the future (Li et al., 2002). Online shoppers rate their satisfaction with various aspects of the shopping experience, including the availability of relevant product information (Hennig-Thurau et al., 2004). These include the ease with which they could make a payment, the speed of order fulfilment, the quality of customer service, the overall level of service, privacy and security measures in place, the uniqueness of their shopping experience and the enjoyment they had while doing so, to name a few (Zeithaml et al., 1996).

Customers’ positive online experiences are the primary factor in expanding e-commerce, claim Elliot and Fowell (2000). For Shim and Drake (1990), it is clear that consumers with a history of positive online purchase experiences have an advantage when making the next purchase decision. More importantly, customers with previous positive online shopping experiences are more likely to purchase than those with negative experiences (Delgadillo & Escalas, 2004). According to Keller et al. (2000), this trend arises because people with some history of online shopping, even if only for modest transactions at first, are more likely to acquire the competence and self-assurance necessary to make larger, more significant purchases online. The expectancy-value model becomes more critical in guiding behaviour when an individual has limited background knowledge of the issues (Chiu et al., 2012a). Customers are more likely to return to online retailers if they have had positive purchasing experiences with them (Azifah & Dewi, 2016). Online shopping has the potential to lose customers if their previous attempts are judged to have been unsuccessful.

For this reason, it is crucial to provide excellent service to current Internet buyers so they will return to the firm’s website in the future (Azifah & Dewi, 2016; Weber & Roehl, 1999). The enormous body of literature suggests that a customer’s previous online buying experience significantly influences their propensity to shop again (Flavián et al., 2017; Hesketh, 2021). However, mass-market brands may have at least one negative purchase experience (Graham & Wilder, 2020). Therefore, the present study aims to examine the impact of negative experiences related to online purchasing/shopping on consumers’ advertising brand experience while watching an ad. Thus, we predict:

H9: Prior online purchase experience moderates the relationship between storytelling ads and advertising behavioural experience.

H10: Prior online purchase experience moderates the relationship between storytelling ads and advertising intellectual experience.

H11: Prior online purchase experience, the relationship between storytelling ads and advertising sensory experience.

H12: Prior online purchase experience moderates the relationship between storytelling ads and advertising affective experience.

Methodology

We used a quasi-experimental design to investigate the effects of storytelling on brand-related outcome variables (Sayar et al., 2018). The experimental method is popular for studying brand storytelling advertising effects (Chiu et al., 2012b; Lien & Chen, 2013) and the advertising experience (Beierwaltes et al., 2020). We also used two existing and professionally produced video storytelling advertising campaigns as stimuli.

Because the advertising messages for these items would alter to represent how customers reach their purchase choice, we have followed the search and experience product paradigm often used in narrative advertising research (Taute et al., 2011; Wang & Calder, 2006b; Woodside, 2010; Zhang et al., 2020). Consider the scenario where customers prioritise product testing before making a choice. In that instance, the item is regarded as an experienced product, necessitating an evocative storytelling ad (Seo et al., 2018). However, if customers prioritise product information while choosing a search product, demonstrating these functional qualities and benefits will be seen as essential (Graham & Wilder, 2020; van Laer et al., 2019).

Stimuli

The search and experience ad paradigm used in the narrative advertising research (Laurence, 2018) as advertising messages for these products shall differ in how consumers make purchasing decisions (Weathers et al., 2007). An emotionally charged storytelling ad is needed if consumers value product experience before buying (Brechman & Purvis, 2015). However, demonstrating these functional attributes and benefits will be critical if consumers value product information when buying search products (Polyorat & Alden, 2005). We avoided the high-versus-low-involvement dichotomy because low-involvement products can be products (like daily-use products) or experienced products (like vehicles).

Our research used full-length, long-duration (Dhote & Kumar, 2019, p. 31) video storytelling advertising campaigns instead of one-page print ads or posters (Escalas, 2004; Mitchell & Clark, 2021). This restriction prevented us from artificially manipulating message elements to create a complex design with too many variables. Narrative advertising studies increasingly use real-world video ads as experimental stimuli (Chen, 2015; Chen & Chang, 2017, p. 22).

Sampling

We recruited 850 student participants using convenient sampling, and 808 participant responses were deemed fit and usable for analysis. After reading and signing the informed consent form, participants were randomly assigned to view a Bajaj or Cadbury advertisement (N = 390 and 418, respectively). 32.4% of the participants were male, while 67.6% were female. Their average age was 24.35 (SD = 5.98) years, and the majority of them (N = 94.3%) were single.

Justifications for the use of student participants in our study are provided below.

First, the student sample would be a concern if the research objectives are to extend these relationships to real-world contexts. However, many narratives and storytelling advertising studies have employed experimental or quasi-experimental (Chen, 2015) methods and easily recruited college students for their research. Second, the existing product usage experience has checked (Frost et al., 2020) and employed the college student population. Thirdly, a strong and plausible match exists between the student participants and the two highlighted products in the experimental stimuli (Ciarlini et al., 2010). Fourth, student participants yield managerially relevant insights because 18 to 24-year-olds are heavy users of social media platforms capable of delivering a great deal of video advertising content. Moreover, 68% of the participants in the same demographic segment use YouTube regularly, while 89% use Instagram and 63% use Snapchat. Our current sample size for each condition is comparable to previously published research (Yoo, 2008).

Measures, Face-Validity and Statistical Software

The online questionnaire included demographic, multidimensional, brand awareness and brand loyalty questions. The three-item narrative transportation scale was adapted from Green and Brock (2000) to measure brand story elements and consumer emotions when reading brand narratives. The experience variable was derived from Huang and Ha (2020). It included a three-item brand sensory experience, a three-item brand intellectual experience, a three-item brand behavioural experience, overall brand equity (Yoo, 2008) and a four-item prior online purchase experience (Hepola et al., 2017). The 5-point Likert scale was used, with one indicating ‘Strongly Disagree’ and five ‘Strongly Agree’. AMOS 20.0, SPSS 25.0 and Excel were used for data analysis.

Data Analysis

Since the questionnaire is the sole tool the researchers are using, Harman’s single factor test was performed to determine whether common method bias was present. For this, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was performed after all the variables’ elements were placed onto a single factor without rotating. The items, response format, instruction, researcher, respondent capability, and motivation all contribute to method bias, as stated by common method bias (CMB) at the start of the measurement procedure. For instance, the questionnaire’s first question may impact a respondent’s response, skewing the results. A two-pronged question or unclear phrase may have confused the respondent. Respondents must use entrenched responses since they can’t create a suitable response. Double-barreled questions are asked to two people. These characteristics cause common variance among indicators, which can hurt inferential statistics. There were no CMB problems (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Additionally, the researchers used the common latent factor approach to confirm the outcome (CLF). Here, the regression weight showed a delta of less than 0.20 for the two models, one with the CLF and the other without the CLF, indicating that the CMB was absent (Ranaweera & Jayawardhena, 2014). No difference in the response of early and late respondents to the survey was observed, thus indicating no issues related to nonresponse bias (Armstrong & Overton, 1977).

Approach to Data Analysis

A two-step approach was applied to analyse the model’s goodness of fit and proposed hypotheses in a single research model using structural equation modelling (SEM) in AMOS 26.0 software. First, we assessed the goodness of fit of the model. On the satisfactory measurement of the model, we examine the indirect and direct relationship between multiple exogenous and endogenous variables by employing the maximum likelihood method and the interaction effect between brand storytelling ads and sympathy. As per Byrne (2016), SEM provides a unique way of assessing the authenticity and consistency of the hypothesised data. Conventional indices such as chi-square, incremental fit indices and absolute fit indices were employed to test the structural models. As suggested by scholars, the following model fit indices were: chi-square (|2)—less than 3 (Byrne, 2006); root means square error of approximation (RMSEA)—less than 0.08 (Hu & Bentler, 1998); comparative fit index (CFI)—greater than 0.90 (Hair et al., 2014); goodness of fit index (GFI)—between 0.80 and 0.90 (Greenspoon & Saklofske, 1998); Tucker-Lewis index (TLI)—greater than 0.90 and Normed Fit Index (NFI)—between 0.80 and 0.90. In addition, the statistical significance of the index of moderated mediation, the moderated mediation and moderated serial-mediation effects were tested at a 95% confidence interval.

Preliminary Analysis

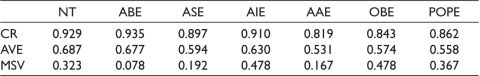

Mean (M), standard deviations (SD) and Cronbach’s α of six variables are presented in Table 1. The figures in Table 1 indicate that all six variables have satisfactory reliabilities. Nunnally (1978) suggested Cronbach’s α needs to be greater than 0.70.

Table 1. Mean, Standard Deviations and Reliabilities.

Abbreviations: NT, narrative transportation; ABE, advertising behavioural experience; ASE, advertising sensory experience; AIE, advertising intellectual experience; AAE, advertising affective experience; OBE, overall brand equity; POPE, prior online purchase experience.

Measurement Model and Validity

In this study item parcels were created for the variables of narrative transportation (11 Items) to reduce the model estimation error and complexity. The online questionnaire included demographic, multidimensional, brand awareness and brand loyalty questions. The three-item narrative transportation scale was adapted from (Green & Brock, 2000) to measure brand story elements and consumer emotions when reading brand narratives. The experience variable was derived from Huang and Ha (2020). It included a three-item brand sensory experience, three-item brand intellectual experience, three-item brand behavioural experience, overall brand equity and four-item prior online purchase experience. Testing of measurement model revealed a good model fit (|2 = 979.9, p = 0.000, |2/df = 2.041, RMSEA = 0.052, CFI = 0.940, GFI = 0.864, NFI = 0.891 and TLI = 0.935). Factor loadings of the observed indicators on the latent variables were significant as p < 0.05, with each construct ranging from 0.645 to 0.912. Table 2 provides composite reliability (CR), average variance extracted (AVE) and square root average variance extracted for the model construct. The reliability of all the latent variables was seen as CR values exceeded the threshold value of 0.60 (Bagozzi & Yi, 1988). AVE was employed for the convergent validity of the model and showed that all the AVE figures exceeded the acceptable criteria of 0.50 (Bagozzi & Yi, 1988; Chin, 1998). Discriminant validity was established where maximum shared variance (MSV) was lower than the average variance extracted (AVE) for all the constructs, indicating acceptable discriminant validity of the measurement model (Chin, 1998).

Table 2. Composite Reliability (CR), Average Variance Extracted (AVE) and Maximum Shared Variance (MSV) for Latent Construct of Measurement Mode.

Abbreviations: ABE, advertising behavioural experience; ASE, advertising sensory experience; NT, narrative transportation; AAE, advertising affective experience; AIE, advertising intellectual experience; OBE, overall brand equity; POPE, prior online purchase experience.

Common Method Bias and Non-response Bias

Self-reported data on various constructs might raise the possibility of common method bias. Therefore, we conducted Harman’s one-factor test (Podsakoff et al., 2003). All items of seven variables were forced to load on a single unrotated factor. The results suggested that the principal factor explained 38.495% of the variance, less than 50%. This shows that a single factor did not capture variance, and the extent of the common method bias is limited. Furthermore, the researchers confirmed the result by executing the standard latent factor method (CLF). Here, the regression weight for the two models, one with the CLF and the other without the CLF, exhibited a delta of less than 0.20, confirming the absence of the common-method variance (Ranaweera & Jayawardhena, 2014). No difference in the response of early and late survey respondents was observed, thus indicating no issues related to nonresponse bias (Armstrong & Overton, 1977). Furthermore, a one-factor model was tested and revealed a good fit to the data (|2 = 1227.13, p = 0.000, |2/df = 1.9025, RMSEA = 0.049, CFI = 0.933, NFI = 0.870 and TLI = 0.923).

Analysis of Structural Model

Maximum likelihood estimate was used in SEM for the present study (Kwon et al., 2005; Anderson & Gerbing, 1988). Results showed that the model attained a good model fit, |2 = 4.9898, p = 0.000, |2/df = 1.247, RMSEA = 0.0257, CFI = 0.998, GFI = 0.997, NFI = 0.995 and TLI = 0.982. Figure 1 shows narrative transportation (NT) ads exerted a strong significant effect on advertising behavioural experience ABE (β = 0.679, p < 0.001) (H1 accepted) and advertising sensory experience (ASE) (β = 0.474, p < 0.001) (H2 accepted). Furthermore, narrative transportation significantly predicts both advertising intellectual experience (AIE) and advertising affective experience (AAE) (β = 0.610, p < 0.001) (H3 Accepted) and (β = 0.506, p < 0.001) (H4 accepted). In addition, advertising sensory experience (ASE) significantly predicts overall brand equity OBE (β = 0.364, p < 0.001) (H5 accepted) but not advertising behavioural experience (β = 0.51, p = 0.628) (H6 accepted). In contrast, advertising intellectual experience (AIE) was a significant predictor of overall brand equity (β = 0.569, p < 0.001) (H7 accepted) and advertising affective experience (AIA) (β = 0.402, p < 0.001) (H8 accepted).

Analysis of Moderation

Criteria stated by Baron & Kenny (1986) were used to test the moderation effect. Where the moderator should not directly relate to the dependent variable, the moderator should practice as an independent variable, and the moderator hypothesis is supported if the interaction is significant. By using moderated structural equation modelling approach, Figure 2 shows that the interaction coefficient is significant (β = 0.05, p < 0.05). Moderation results were further confirmed with a slope test to examine the effect of prior online purchase experience (POPE) on narrative transportation for one standard deviation with all advertising behavioural constructs. As per Cohen (1983), the relationship between narrative transportation and advertising behaviour is lower when the prior online purchase experience (POPE) is higher (β = 0.401, t = 6.597 p < 0.05). Thus, H9 is supported.

Figure 1. Proposed Research Model.

Figure 2. The Research Model.

Note: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001; Solid Lines Indicates Significant Paths and Dotted Line Indicate Non-Significant, for Which Path Coefficient Are Not Shown.

Furthermore, the interaction coefficient is significant (β = 0.062, p < 0.05) toward advertising attitude. Further, the slope test confirmed the effect of brand storytelling ads on advertising attitude with one standard deviation above and below the level of sympathy. The relationship between narrative transportation and advertising sensory, intellectual and affective is higher when the prior online purchase experience (POPE) is lower. Thus, H10, H11 and H12 were not supported, and POPE did not moderate consumers’ affective, sensory and intellectual experience while watching an advertisement.

Discussion

Advertising Experience and Narrative Storytelling

Our findings indicate the positive impact of ad-elicited narratives on aspects of the advertising experience and confirm that storytelling video ad impacts viewers’ experiences and positively impacts overall brand equity. Once advertising communi- cations create narrative transportation, they can increase brand awareness, loyalty and perceived worth independent of the product or platform. Customers can easily be transported to the fictional world by watching video storytelling advertising, leaving society behind, as an innovative approach to stimulate their neural activity (Escalas, 2004). Due to its lengthy style, video narrative advertising is convincing and creative (Trivedi & Trivedi, 2018). These effects can enhance the brand’s behavioural, sensory, intellectual and affective experience due to prolonged exposure to advertisements. Transportation should be viewed from a cognitive perspective as an active ‘participatory response’ (Wang & Calder, 2006b, p. 406) that enables consumers to form thoughts when exposed to the video narrative ad, probably providing a more positive advertising experience. Consumers can use dramatisation and illustration to visualise a product’s advantages (Zwack et al., 2016). Customers are ‘pulled into a story wonderfully and actively’ (Wang et al., 2006a, p. 406) while experiencing a video storytelling advertisement, allowing them to virtually experience the brand. For instance, the chocolate commercial’s heartfelt song and romantic story may remind viewers of their first love. Transportation probably enhances the advertising customer experiences (Phillips & McQuarrie, 2010).

Escalas (2004) describes constructing an advertising brand experience after narrative processing. Personal experiences are connected to the brand narrative project by customer interpretations. We postulate that storytelling evocation brought on by video storytelling advertisements can aid viewers in recalling ‘autobiographical memories’ or simulating potential romantic encounters (Tattam, 2010). For example, a chocolate campaign may inspire young consumers to think about what lies ahead or remind many older consumers about their first love from high school, creating an ‘affect transfer’ (Grigsby & Mellema, 2020). This strengthens consumer relationships with the advertised brand and fosters a more satisfying sensory advertising brand experience (Hepola et al., 2017). These techniques can be used to explain the beneficial correlations between the advertising impression and storytelling conveyance in video advertisements.

Whether or not customers can connect with an advertised brand can be attributed to the positive effects of narrative transportation. Video storytelling advertising gives consumers a dynamic platform for brand involvement (Hollebeek et al., 2014). Customers may relate to what characters experience in a video storytelling advertising campaign that depicts how characters engage with the brand in a story event, creating the company’s experiencing meaning (Kehrli, 2021) or instrumental meaning (Mollen & Wilson, 2010). Instrumental and experiential brand meanings can boost the sensory and intellectual brand experience. To ‘personally experience’ the benefits of a product, consumers relate to what a brand storytelling character (or characters) may have gone through and indirectly engage in such events (Boller & Olson, 1991). Our findings indicate that video storytelling ads have a more significant effect on customers’ intellectual and affective brand perceptions via brand interactions as described in both of the video storytelling campaigns in this study (high path coefficient in brand sensory experience, [β = 0.51]).

Overall Brand Equity

Video storytelling ads help consumers discover a brand’s consistent and appealing content. Cognitive and behavioural brand experiences will spark customers’ overall brand equity (Huang et al., 2011), which includes perceived worth, brand loyalty and awareness (He, 2014). According to a previous study, prevalent brand equity explains 37% of brand loyalty variance. Our analysis shows that brand loyalty variance is 36% predictive. Like Huang, the brand’s intellectual experience was the most potent predictor of the experiential product’s advertising experience (β = 0.56). For instance, when customers choose a brand, if the brand stimulates [their] curiosity and makes [them] think, it is vital to their intellectual experience. Hence, marketers must build story tactics to elicit diverse brand experiences. Our results do not support Huang and Ha’s (2020) clinically important finding that corporate behaviour based on behavioural experience and brand equity are statistically associated. Only experience products are included in Huang’s survey so that participants can assess claims about brand behaviour. Based on three Likert statements, Cadbury, a chocolate brand, in our study may be considered ‘action-oriented’ since it ‘engages [consumers] in physical patterns of behaviour when I use this brand’ or ‘results in behaviour experiences’. However, in the case of Bajaj, an Indian automobile company, they can be moved by an advertisement, but it does not translate into consumers making a purchase. Our study supports the model’s positive correlations between advertising sensory and intellectual experiences on brand equity (Hwang et al., 2016; Pera, 2017). Sensory advertising experience predicts liking for experience products. Our findings suggest that brand equity is a long-term effect triggered by an emotionally intense video narrative ad.

Positive advertising sensory experience and brand equity may be attributed to whether watching these video storytelling commercials affects consumers’ information processing and persuasive effects (Lim & Childs, 2020). Emotionally charged video narrative advertising may alter people’s emotions when behavioural advertising experiences affect product appraisal and buying intention (Wanggren, 2016). Marketing literature has examined the impact of advertising experiences on loyalty, however, studies have yet to explore the influence of advertising experience on brand equity as an experience-based antecedent. Similarly, Nuske and Hing (2013) and Zhang et al. (2020) demonstrated how behavioural experience significantly influenced brand loyalty; however, the study did not examine brand equity.

Our study focused on the influence of consumers’ intellectual, sensory and affective experiences on brand equity, whereas prior studies focused solely on behavioural experiences (Zhang et al., 2020). Our findings help clarify ad-induced advertising brand experience and its implications for creating high brand equity (Machado et al., 2019).

Conclusion

Offering lengthy or short video storytelling is one of the advantages of video advertising via YouTube and other popular social media platforms. Traditional television advertising, on the other hand, is typically limited in length (Suarezserna, 2020). Additionally, the price of prolonged branded advertising material may not always be higher than that of standard television advertising (Kaushik & Soch, 2021). Due to these benefits, video narrative advertising is more cost-effective and creative than conventional advertising. Continuous exposure to video storytelling advertisements causes narrative transportation, which is more successful at influencing consumers (Hepola et al., 2017). Notably, its impacts are not limited by the sorts of offered products, indicating that narrative transfer is a robust and consistent predictor of consumer advertising brand experience. The findings also suggest that video narrative advertising could be an effective creative strategy for several product categories. Moreover, after a bad online purchase experience, if a brand uses effective narrative techniques, it can improve (recover) overall brand equity using a positive sensory, affective and intellectual advertis- ing experience. Moreover, storytelling may or may not impact their behavioural actions toward the brand.

Managerial and Theoretical Implications

The present study contributes to the literature in several ways. First, we diverge from the methods and theoretical underpinnings used in recent narrative advertising works (Koll et al., 2010). The concept that narrative mobility might also impact factors associated with brand outcomes has largely been ignored in advertising research. As a result of narrative transportation, the marketing journey as subjective and behavioural responses to ad stimuli are rarely studied in the existing narrative advertising literature (Loureiro et al., 2019). Customers are likely to be transported into a state of experience that allows them to engage in the story itself instead of focusing on any ramifications outside the story when they are given a tale about a business through one-minute video advertising (Chen & Chang, 2017, p. 28). Positive brand experiences can be produced through engaging with branded content and interacting with a brand. Despite the prior concept of narrative transportation’s reliance on experience, advertising professionals have yet to connect narrative transportation with the advertising brand experience. By connecting narrative transportation with advertising experience and overall brand equity, our work could potentially bridge the traditional research areas in narrative advertising and brand management. It is also interesting to notice that the favourable impact of narrative transportation does not differ significantly between search/functional and experiential products, indicating that narrative transportation has a significant effect on branding outcomes. This study’s findings can help other researchers analyse whether narrative transportation survives in high-involvement products, products consumed in public or private settings or products imported from foreign nations.

From a managerial perspective, we have shown the value of ad-evoked narrative transport as a strategic approach for both search and experience products. We further underline that advertising brand experience is crucial for enhancing perceived worth, awareness and loyalty (Ten Brug et al., 2015). In addition, this study establishes a link between narrative advertising and brand management by demonstrating that marketers can enhance the advertising experience of consumers by developing compelling brand-storytelling advertisements to construct an effective brand management plan. Advertising experiences prompted by a compelling story can be as practical as other marketing strategies in generating positive brand outcomes, particularly when a brand wants to target customers who have had one or two negative online purchase experiences. With this strategy, marketers can prevent customers from hating/disliking brands solely due to negative online purchase experiences.

Limitations and Future Directions for Research

There are various limitations associated with the interpretation of the results of this study. First, the external validity of the study’s findings cannot be extrapolated to other product categories. We have confined our research to two, high and low, involvement categories. These findings should be separate from other product categories with different levels of engagement. Using a video storytelling platform to provide branded narratives to customers presents a further constraint. Previously, we emphasised that many researchers have used print or poster advertisements as experimental stimuli; nevertheless, these two-dimensional print ad stimuli are significantly limited in their ability to elicit emotions in participants, even if primed during the experiment. However, modern integrated marketing communication efforts give branded material to consumers via various touchpoints. Lastly, our reliance on the Indian management student sample will limit the applicability of our findings to other consumer sectors worldwide. Our sampling selection is based on previous story advertising research in which students were recruited for the study. However, a portion of our selection also considers the heavy video content users among the student population, whose responses will be managerially valuable.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Aaker, J. L., Garbinsky, E. N., & Vohs, K. D. (2012). Cultivating admiration in brands: Warmth, competence, and landing in the ‘golden quadrant’. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 22(2), 191–194.

Alexandrakis, D., Chorianopoulos, K., & Tselios, N. (2020). Older adults and Web 2.0 storytelling technologies: Probing the technology acceptance model through an age-related perspective. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 36(17), 1623–1635. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2020.1768673

An, D., Lee, C., Kim, J., & Youn, N. (2020). Grotesque imagery enhances the persuasiveness of luxury brand advertising. International Journal of Advertising, 39(6), 783–801.

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411.

Armstrong, J. S., & Overton, T. S. (1977). Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. Journal of Marketing Research, 14(3), 396–402.

Azifah, N., & Dewi, C. K. (2016). Pengaruh shopping orientation, online trust dan prior online purchase experience terhadap online purchase intention (Studi pada Online Shop Hijabi House). Bina Ekonomi, 20(2), 115–126.

Barcelos, C., & Gubrium, A. (2018). Bodies that tell: Embodying teen pregnancy through digital storytelling. Signs, 43(4), 905–927. https://doi.org/10.1086/696627

Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 16, 74–94.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173.

Beierwaltes, P., Clisbee, D., & Eggenberger, S. K. (2020). An educational intervention incorporating digital storytelling to implement family nursing practice in acute care settings. Journal of Family Nursing, 26(3), 213–228. https://doi.org/10.1177/1074840720935462

Berezkin, R. (2013). The transformation of historical material in religious storytelling: The story of Huang Chao (D. 884) in the baojuan of Mulian rescuing his mother in three rebirths. Late Imperial China, 34(2), 83–133. https://doi.org/10.1353/late.2013.0008

Betty, X. (2020). Plantemic: A philosophical inquiry and storytelling project about human–plant co-existence during the COVID-19 pandemic. https://openresearch.ocadu.ca/id/eprint/3168/

Bhattacharya, C. B., Rao, H., & Glynn, M. A. (1995). Understanding the bond of identification: An investigation of its correlates among art museum members. Journal of Marketing, 59(4), 46–57.

Boller, G. W., & Olson, J. C. (1991). Experiencing ad meanings: Crucial aspects of narrative/drama processing. ACR North American Advances, 18, 164–171. https://www.acrwebsite.org/volumes/7156/volumes/v18/NA-18

Bordahl, V. (2003). The storyteller’s manner in Chinese storytelling (Vernacular novel and short story). Asian Folklore Studies, 62(1), 65–112.

Brechman, J. M., & Purvis, S. C. (2015). Narrative, transportation and advertising. International Journal of Advertising, 34(2), 366–381.

Byrne, B. M. (2016). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Routledge.

Chen, K. K. (2013). Storytelling: An Informal mechanism of accountability for voluntary organizations. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 42(5), 902–922. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764012455699

Chen, N. T. N., Dong, F., Ball-Rokeach, S. J., Parks, M., & Huang, J. (2012). Building a new media platform for local storytelling and civic engagement in ethnically diverse neighborhoods. New Media & Society, 14(6), 931–950. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444811435640

Chen, T. (2015). The persuasive effectiveness of mini-films: Narrative transportation and fantasy proneness. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 14(1), 21–27.

Chen, T., & Chang, H.-C. (2017). The effect of narrative transportation in mini-film advertising on reducing counterarguing. International Journal of Electronic Commerce Studies, 8(1), 25–46.

Chin, W. W. (1998). Commentary: Issues and opinion on structural equation modeling. MIS Quarterly, 22(1), vii–xvi.

Chiu, C.-M., Hsu, M.-H., Lai, H., & Chang, C.-M. (2012a). Re-examining the influence of trust on online repeat purchase intention: The moderating role of habit and its antecedents. Decision Support Systems, 53(4), 835–845.

Chiu, H.-C., Hsieh, Y.-C., & Kuo, Y.-C. (2012b). How to align your brand stories with your products. Journal of Retailing, 88(2), 262–275.

Ciarlini, A. E. M., Casanova, M. A., Furtado, A. L., & Veloso, P. A. S. (2010). Modeling interactive storytelling genres as application domains. Journal of Intelligent Information Systems, 35(3), 347–381. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10844-009-0108-5

Cohen, J. (1983). The cost of dichotomization. Applied Psychological Measurement, 7(3), 249–253.

Curenton, S. M., Craig, M. J., & Flanigan, N. (2008). Use of decontextualized talk across story contexts: How oral storytelling and emergent reading can scaffold children’s development. Early Education and Development, 19(1), 161–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409280701839296

da Silva, E. R., & Larentis, F. (2022). Storytelling from experience to reflection: ERSML cycle of organizational learning. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2020.1737831

Delgadillo, Y., & Escalas, J. E. (2004). Narrative word-of-mouth communication: Exploring memory and attitude effects of consumer storytelling. In B. E. Kahn & M. F. Luce (Eds.), Advances in consumer research (Vol. 31, pp. 186–192). Association for Consumer Research.

Dhote, T., & Kumar, V. (2019). Long-duration storytelling: Study of factors influencing retention ability of brands. Journal of Creative Communications, 14(1), 31-53.

Elliot, S., & Fowell, S. (2000). Expectations versus reality: A snapshot of consumer experiences with Internet retailing. International Journal of Information Management, 20(5), 323–336.

Escalas, J. E. (2003). Advertising narratives: What are they and how do they work? In Representing consumers (pp. 283–305). Routledge.

Escalas, J. E. (2004). Imagine yourself in the product: Mental simulation, narrative transportation, and persuasion. Journal of Advertising, 33(2), 37–48.

Flavián, C., Gurrea, R., & Orús, C. (2017). The influence of online product presentation videos on persuasion and purchase channel preference: The role of imagery fluency and need for touch. Telematics and Informatics, 34(8), 1544–1556.

Fog, K., Budtz, C., & Yakaboylu, B. (2005). Storytelling. Springer.

Frost, W., Frost, J., Strickland, P., & Maguire, J. S. (2020). Seeking a competitive advantage in wine tourism: Heritage and storytelling at the cellar-door. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 87 (9), 102460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102460

Godey, B., Manthiou, A., Pederzoli, D., Rokka, J., Aiello, G., Donvito, R., & Singh, R. (2016). Social media marketing efforts of luxury brands: Influence on brand equity and consumer behavior. Journal of Business Research, 69(12), 5833–5841.

Graham, K. W., & Wilder, K. M. (2020). Consumer-brand identity and online advertising message elaboration Effect on attitudes, purchase intent and willingness to share. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 14(1), 111–132. https://doi.org/10.1108/jrim-01-2019-0011

Green, M. C., & Brock, T. C. (2000). The role of transportation in the persuasiveness of public narratives. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(5), 701.

Greenspoon, P. J., & Saklofske, D. H. (1998). Confirmatory factor analysis of the multidimensional students’ life satisfaction scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 25(5), 965–971.

Grigsby, J. L., & Mellema, H. N. (2020). Negative consequences of storytelling in native advertising. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 52, 61–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2020.03.005

Hagarty, D. E., & Clark, D. J. (2009). Using imagery and storytelling to educate outpatients about 12-step programs and improve their participation in community-based programs . Journal of Addictions Nursing, 20(2), 86–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/10884600902850129

Hair Jr, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Hopkins, L., & G. Kuppelwieser, V. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) An emerging tool in business research. European Business Review, 26(2), 106–121.

Haring, L. (2003). Techniques of creolization (Storytelling, oral texts). Journal of American Folklore, 116(459), 19–35. https://doi.org/10.1353/jaf.2003.0010

He, Q. L. (2014). Between accommodation and resistance: Pingtan storytelling in 1960s Shanghai. Modern Asian Studies, 48(3), 524–549. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0026749x12000789

Hennig-Thurau, T., Gwinner, K. P., Walsh, G., & Gremler, D. D. (2004). Electronic word-of-mouth via consumer-opinion platforms: What motivates consumers to articulate themselves on the internet? Journal of Interactive Marketing, 18(1), 38–52.

Hepola, J., Karjaluoto, H., & Hintikka, A. (2017). The effect of sensory Advertising brand experience and involvement on brand equity directly and indirectly through consumer brand engagement. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 26(3). http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-10-2016-1348

Hesketh, J. I. (2021). Why I need that: How identity-based relationships between viewer, film, and product can lead to purchase behaviour (28495644, ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global). Fielding Graduate University.

Hollebeek, L. D., Glynn, M. S., & Brodie, R. J. (2014). Consumer brand engagement in social media: Conceptualization, scale development and validation. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 28(2), 149–165.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1998). Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods, 3(4), 424.

Huang, J., Song, H., & Bargh, J. (2011). Debiasing effect of fluency on linear trend prediction. ACR North American Advances. https://www.acrwebsite.org/volumes/16073/volumes/v38/NA-38

Huang, R., & Ha, S. (2020). The role of need for cognition in consumers’ mental imagery: A study of retail brand’s Instagram. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/IJRDM-04-2020-0146

Huang, S., & Yang, J. (2015). Contracting under asymmetric customer returns information and market valuation with advertising-dependent demand. European Journal of Industrial Engineering, 9(4), 538–560. https://doi.org/10.1504/ejie.2015.070325

Hung, C. M., Hwang, G. J., & Huang, I. (2012). A project-based digital storytelling approach for improving students’ learning motivation, problem-solving competence and learning achievement. Educational Technology & Society, 15(4), 368–379.

Hwang, W. Y., Shadiev, R., Hsu, J. L., Huang, Y. M., Hsu, G. L., & Lin, Y. C. (2016). Effects of storytelling to facilitate EFL speaking using Web-based multimedia system. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 29(2), 215–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2014.927367

Iurgel, I. A. (2003). Virtual actors in interactivated storytelling. In T. Rist, R. Aylett, D. Ballin, & J. Rickel (Eds.), Intelligent virtual agents (Vol. 2792, pp. 254–258). Springer-Verlag.

Kang, J. A., Hong, S., & Hubbard, G. T. (2020). The role of storytelling in advertising: Consumer emotion, narrative engagement level, and word-of-mouth intention. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 19(1), 47–56. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.1793

Kang, S., Ko, H., & Choy, Y. (2006). 4-dimensional context management for interactive virtual storytelling. In Z. G. Pan, H. Diener, X. G. Jin, S. Gobel, & L. Li (Eds.), Technologies for E-Learning and digital entertainment, proceedings (Vol. 3942, pp. 438–443). Springer-Verlag.

Kaushik, P., & Soch, H. (2021). Interaction between brand trust and customer brand engagement as a determinant of brand equity. International Journal of Technology Transfer and Commercialisation, 18(1), 94–108.

Kehrli, M. K. (2021). Composing a narrative: A life history of Mary Pemble Barton through her storied legacy (28720317, ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global). Drake University.

Keller, A. A., Sakthivadivel, R., & Seckler, D. W. (2000). Water scarcity and the role of storage in development (Vol. 39). IWMI.

Keller, M. W. (2020). An appetite for the tasteless: An evaluation of off-color humor in adult animations and video games, presented through a proposed interactive narrative via a procedurally generated material Library (28256670, ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global). Clemson University.

Koenig, J. M., & Zorn, C. R. (2002). Using storytelling as an approach to teaching and learning with diverse students. Journal of Nursing Education, 41(9), 393–399.

Koll, O., von Wallpach, S., & Kreuzer, M. (2010). Multi-method research on consumer-brand associations: Comparing free associations, storytelling, and collages. Psychology & Marketing, 27(6), 584–602. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20346

Kwon, H. H., Trail, G. T., & Anderson, D. S. (2005). Are multiple points of attachment necessary to predict cognitive, affective, conative, or behavioral loyalty? Sport Management Review, 8(3), 255–270.

Laurence, D. (2018). Do ads that tell a story always perform better? The role of character identification and character type in storytelling ads. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 35(2), 289–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2017.12.009

Lee, E. B., Lee, S. G., & Yang, C. G. (2017). The influences of advertisement attitude and brand attitude on purchase intention of smartphone advertising. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 117(6), 1011–1036. https://doi.org/10.1108/imds-06-2016-0229

Lee, H., & Jahng, M. R. (2020). The role of storytelling in crisis communication: A test of crisis severity, crisis responsibility, and organizational trust. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 97(4), 981–1002. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699020923607

Lee, Y., Oh, S., & Woo, W. (2005). A context-based storytelling with a responsive multimedia system (RMS). In G. Subsol (Ed.), Virtual storytelling: Using virtual reality technologies for storytelling, proceedings (Vol. 3805, pp. 12–21). Springer-Verlag.

Li, H. R., Daugherty, T., & Biocca, F. (2002). Impact of 3-D advertising on product knowledge, brand attitude, and purchase intention: The mediating role of presence. Journal of Advertising, 31(3), 43–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2002.10673675

Lien, N. H., & Chen, Y. L. (2013). Narrative ads: The effect of argument strength and story format. Journal of Business Research, 66(4), 516–522.

Lim, H., & Childs, M. (2020). Visual storytelling on Instagram: Branded photo narrative and the role of telepresence. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 14(1), 33–50. https://doi.org/10.1108/jrim-09-2018-0115

Liu, C. C., Liu, K. P., Chen, W. H., Lin, C. P., & Chen, G. D. (2011). Collaborative storytelling experiences in social media: Influence of peer-assistance mechanisms. Computers & Education, 57(2), 1544–1556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2011.02.002

Loureiro, S. M. C., Bilro, R. G., & Japutra, A. (2019). The effect of consumer-generated media stimuli on emotions and consumer brand engagement. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 29(3), 387–408.

Lundqvist, A., Liljander, V., Gummerus, J., & Van Riel, A. (2013). The impact of storytelling on the consumer brand experience: The case of a firm-originated story. Journal of Brand Management, 20(4), 283–297.

Machado, J. C., Vacas-de-Carvalho, L., Azar, S. L., André, A. R., & dos Santos, B. P. (2019). Brand gender and consumer-based brand equity on Facebook: The mediating role of consumer-brand engagement and brand love. Journal of Business Research, 96, 376–385.

Mazzocco, P. J., Green, M. C., Sasota, J. A., & Jones, N. W. (2010). This story is not for everyone: Transportability and narrative persuasion. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 1(4), 361–368.

McEwen, R., Zbitnew, A., & Chatsick, J. (2016). Through the lens of a tetrad: Visual storytelling on tablets. Educational Technology & Society, 19(1), 100–112.

Mitchell, S. L., & Clark, M. (2021). Telling a different story: How nonprofit organizations reveal strategic purpose through storytelling. Psychology & Marketing, 38(1), 142–158. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21429

Mollen, A., & Wilson, H. (2010). Engagement, telepresence and interactivity in online consumer experience: Reconciling scholastic and managerial perspectives. Journal of Business Research, 63(9–10), 919–925.

Nilsen. (2022). In a streaming-first world, comparable, always on measurement is critical.?https://www.nielsen.com/insights/2022/in-a-streaming-first-world-comparable-always-on-measurement-is-critical/

Nielsen. (n.d.). Nielsen’s 2022 Global Annual Marketing Report–Era of Alignment. Retrieved November 12, 2022, from https://annualmarketingreport.nielsen.com?lang=en

Nunnally, J. C. (1978). An overview of psychological measurement. In B. B. Wolman (Ed.), Clinical diagnosis of mental disorders: A handbook (pp. 97–146). Springer.

Nuske, E., & Hing, N. (2013). A narrative analysis of help-seeking behaviour and critical change points for recovering problem gamblers: The power of storytelling. Australian Social Work, 66(1), 39–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407x.2012.715656

Ohanian, R. (1990). Construction and validation of a scale to measure celebrity endorsers’ perceived expertise, trustworthiness, and attractiveness. Journal of Advertising, 19(3), 39–52.

Papacharissi, Z., & Oliveira, M. D. (2012). Affective news and networked publics: The rhythms of news storytelling on #Egypt. Journal of Communication, 62(2), 266–282. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2012.01630.x

Pera, R. (2017). Empowering the new traveller: Storytelling as a co-creative behaviour in tourism. Current Issues in Tourism, 20(4), 331–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500. 2014.982520

Pera, R., & Viglia, G. (2016). Exploring how video digital storytelling builds relationship experiences. Psychology & Marketing, 33(12), 1142–1150. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20951

Phillips, B. J., & McQuarrie, E. F. (2010). Narrative and persuasion in fashion advertising. Journal of Consumer Research, 37(3), 368–392.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879.

Polletta, F., & Callahan, J. (2017). Deep stories, nostalgia narratives, and fake news: Storytelling in the Trump era. American Journal of Cultural Sociology, 5(3), 392–408. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41290-017-0037-7

Polyorat, K., & Alden, D. L. (2005). Self-construal and need-for-cognition effects on brand attitudes and purchase intentions in response to comparative advertising in Thailand and the United States. Journal of Advertising, 34(1), 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 00913367.2005.10639179

Ramon, M. (2021). Advertising, affect, and the avant-garde: The aesthetics of interruption and identity formation in American fiction of the 1920s (28768039, ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global). University of California, Irvine.

Ranaweera, C., & Jayawardhena, C. (2014). Talk up or criticize? Customer responses to WOM about competitors during social interactions. Journal of Business Research, 67(12), 2645–2656.

Rossolatos, G. (2020). A brand storytelling approach to Covid-19’s terrorealization: Cartographing the narrative space of a global pandemic. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 18(10), 100484. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2020.100484

Ryu, K., Lehto, X. Y., Gordon, S. E., & Fu, X. (2018). Compelling brand storytelling for luxury hotels. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 74, 22–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.02.002

Sangalang, A., Johnson, J. M. Q., & Ciancio, K. E. (2013). Exploring audience involvement with an interactive narrative: Implications for incorporating transmedia storytelling into entertainment-education campaigns. Critical Arts-South-North Cultural and Media Studies, 27(1), 127–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2013.766977

Sawhney, M., Verona, G., & Prandelli, E. (2005). Collaborating to create: The internet as a platform for customer engagement in product innovation. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 19(4), 4–17.

Sayar, S., Tahmasebi, R., Azodi, P., Tamimi, T., & Jahanpour, F. (2018). The impact of tacit knowledge transfer through storytelling on nurses’ clinical decision making. Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal, 20(5), e65732. https://doi.org/10.5812/ircmj.65732

Seifert, C., & Chattaraman, V. (2020). A picture is worth a thousand words! How visual storytelling transforms the aesthetic experience of novel designs. Journal of Product & Brand Management. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-01-2019-2194

Seo, Y., Li, X., Choi, Y. K., & Yoon, S. (2018). Narrative transportation and paratextual features of social media in viral advertising. Journal of Advertising, 47(1), 83–95.

Shim, S., & Drake, M. F. (1990). Consumer intention to utilize electronic shopping. The Fishbein behavioral intention model. Journal of Direct Marketing, 4(3), 22–33.

Suarezserna, F. (2020). Once upon a time… How stories strengthen brands (28261648, ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global). EGADE Business School, Instituto Tecnologico y de Estudios Superiores de Monterrey.

Tattam, H. (2010). Storytelling as philosophy: The case of Gabriel Marcel. Romance Studies, 28(4), 223–234. https://doi.org/10.1179/174581510x12817121842010

Taute, H. A., McQuitty, S., & Sautter, E. P. (2011). Emotional information management and responses to emotional appeals. Journal of Advertising, 40(3), 31–44.

Ten Brug, A., Munde, V. S., van der Putten, A. A. J., & Vlaskamp, C. (2015). Look closer: The alertness of people with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities during multi-sensory storytelling, a time sequential analysis. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 30(4), 535–550. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2015.1046754

Trivedi, J. P., & Trivedi, H. (2018). Investigating the factors that make a fashion app successful: The moderating role of personalization. Journal of Internet Commerce, 17(2), 170–187.

Urgesi, C., Mattiassi, A. D. A., Buiatti, T., & Marini, A. (2016). Tell it to a child! A brain stimulation study of the role of left inferior frontal gyrus in emotion regulation during storytelling. Neuroimage, 136, 26–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.05.039

van Laer, T., Feiereisen, S., & Visconti, L. M. (2019). Storytelling in the digital era: A meta-analysis of relevant moderators of the narrative transportation effect. Journal of Business Research, 96, 135–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.10.053

Wang, D. L., Zhang, J., & Dai, G. Z. (2006a). A multimodal fusion framework for children’s storytelling systems. In Z. G. Pan, H. Diener, X. G. Jin, S. Gobel, & L. Li (Eds.), Technologies for E-Learning and digital entertainment, proceedings (Vol. 3942, pp. 585–588). Springer-Verlag.

Wang, J., & Calder, B. J. (2006b). Media transportation and advertising. Journal of Consumer Research, 33(2), 151–162.

Wang, Q., Koh, J. B. K., & Song, Q. F. (2015). Meaning making through personal storytelling: Narrative research in the Asian American context. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 6(1), 88–96. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037317

Wanggren, L. (2016). Our stories matter: Storytelling and social justice in the Hollaback! movement. Gender and Education, 28(3), 401–415. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253. 2016.1169251

Weathers, D., Sharma, S., & Wood, S. L. (2007). Effects of online communication practices on consumer perceptions of performance uncertainty for search and experience goods. Journal of Retailing, 83(4), 393–401.

Weber, K., & Roehl, W. S. (1999). Profiling people searching for and purchasing travel products on the World Wide Web. Journal of Travel Research, 37(3), 291–298.

Woodside, A. G. (2010). Brand-consumer storytelling theory and research: Introduction to a psychology & marketing Special Issue. Psychology & Marketing, 27(6), 531–540. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20342

Woodside, A. G., Sood, S., & Miller, K. E. (2008). When consumers and brands talk: Storytelling theory and research in psychology and marketing. Psychology & Marketing, 25(2), 97–145. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20203

Xu, Z., Liu, Y. H., Zhang, H., Luo, X. F., Mei, L., & Hu, C. P. (2017). Building the multi-modal storytelling of urban emergency events based on crowdsensing of social media analytics . Mobile Networks & Applications, 22(2), 218–227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11036-016-0789-2

Yoo, C. Y. (2008). Unconscious processing of Web advertising: Effects on implicit memory, attitude toward the brand, and consideration set. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 22(2), 2–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/dir.20110

Zeithaml, V. A., Berry, L. L., & Parasuraman, A. (1996). The behavioral consequences of service quality. Journal of Marketing, 60(2), 31–46.

Zhang, H. X., Zheng, X. Y., & Zhang, X. (2020). Warmth effect in advertising: The effect of male endorsers’ warmth on brand attitude. International Journal of Advertising, 39(8), 1228–1251. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2020.1763089

Zwack, M., Kraiczy, N. D., von Schlippe, A., & Hack, A. (2016). Storytelling and cultural family value transmission: Value perception of stories in family firms. Management Learning, 47(5), 590–614. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350507616659833