1 The Business School, University of Jammu, Jammu and Kashmir, India

Creative Commons Non Commercial CC BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License (http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-Commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed.

Technical advancements that are generating new products, services and markets, at a fast pace tend to meet modern consumer wants. Despite the fact that digital technologies are intangible, users of virtual environments form strong emotional bonds with their goods and frequently experience a sense of psychological ownership of these tools. These digital advances have substantially disrupted psychological ownership since they have replaced legal ownership with legal access rights to things, which has added value for consumers and firms. As a result, in depth study is needed in the field of psychological ownership since it would give more insights and implementable marketing strategies to organisations who wish to capitalise on psychological ownership’s advantages in the digital age. The research presented in this study offers a fresh viewpoint on how consumers’ emotions impact the psychological ownership of digital technologies. The theoretical explanation of the relationship between emotions and psychological ownership is provided in this study, which contends that both factors are essential to producing favourable results for digital enterprises. The research sums up by offering practical marketing tactics for firms looking to maintain the advantages of increased psychological ownership. Additionally, as potential areas for future research, this study calls on academics to do empirical research.

Psychological ownership, emotions, digital technologies, consumer marketing

Introduction

As in modern times, technological innovations are rapidly changing the consumption pattern of goods and services wherein, consumption is evolving from legally owned private material goods to access-based usage in which people purchase temporary rights to use shared goods (Bardhi & Eckhardt, 2012; Eckhardt et al., 2019; Morewedge et al., 2021). The upcoming growth of trends in marketing like the digital sharing economy, digitisation of goods and services, disruptive technologies, access-based consumption of digital services for sustainable behaviour, ever-growing online era (Matzler et al., 2015; Morewedge et al., 2021; Peck & Luangrath, 2023) have put forward the new fashion for the future researchers to probe the psychological ownership aspect of these trends.

In the current scenario of digital advancements, consumer psychology has become a significant and productive topic of discussion and research in digital marketing. Customers’ mental processes and decision-making processes are predicted by marketers using the concept of consumer psychology. The interaction that customers have with technology has evolved into an essential promise in today’s the technology-mediated environment. New products, services and markets are being created as a result of the rapid innovation and advancement of digital technology (Morewedge et al., 2021). Both consumers and businesses gain enormous value from these developments.

Customers have a psychological sense of ownership over digital technologies like online music, films, e-books, online games, etc. According to Watkins and Molesworth (2012), researchers refer to new targets of psychological ownership, which are distinct to the digital realm when they use the term ‘digital virtual products’. These include social media sites, online gaming consoles, online learning platforms, e-books, online shopping and many more. Also, according to consumer psychology, users of digital products and services experience a strong sense of psychological ownership over them (Kirk & Swain, 2018). Consumers feel as though they are the legal owners of these objects even when they are not (Watkins & Molesworth, 2012).

Customers’ view that makes them believe to own the product is known as psychological ownership. These things could be tangible or intangible, physical or immaterial and legally possessed or not (Nijs et al., 2021). Customers frequently form close bonds with the items in their immediate environment and may even feel a sense of psychological ownership. The mental state in which consumers feel the target of possession is ‘theirs’ might thus be described as psychological ownership (Pierce et al., 2001). When consumers put their time and energy into a target (Kamleitner & Erki, 2013), exert control over a target (Peck et al., 2013), or get intimate knowledge of a target (Kirk et al., 2018), they begin to experience an attachment to the object.

Moreover, marketing literature has clearly demonstrated that emotions play a crucial role in affecting the minds of the customer because they have the power to bring about psychological and behavioural change (Kim et al., 2015). Psychological ownership is said to have both cognitive and affective components (Pierce et al., 2003). Positive motivating emotions including pleasure, hope, pride and excitement are believed to encourage psychological ownership. Accordingly, psychological ownership is a result of individual emotions (Baumeister & Wangenheim, 2014). Today firms pay more attention to the emotional reactions towards a product that can elicit more than just its utilitarian advantages. As a result, through emotions, the consumer develops a strong psychological attachment to the product or service. Despite this, there is still little information about how emotions relate to psychological ownership in the digital world and business outcomes (Sinclair & Tinson, 2017).

Objective of the Study

The main objectives of the study are:

1. To propose a theoretical framework that explains the existence of psychological ownership in digital technologies.

2. To theoretically examine the role of emotions in enhancing the psychological ownership of digital products and services.

Review of Literature

Psychological Ownership

The concept of psychological ownership was first studied in the field of management at the beginning of the 21st century (Pierce et al., 2003, 2001). To better understand the relationship between customers and products, psychological ownership has recently flourished in marketing and is supposed to be essential in consumer behaviour (Jussila et al., 2015; Li & Atkinson, 2020; Peck & Shu, 2018).

Psychological ownership has mostly been studied in relation to consumer behaviour. According to (Pierce et al., 2001, 2003), psychological ownership is a cognitive-affective mental state in which a consumer feels a sense of ownership for a target object that is viewed as separate from actual legal possession. Psychological ownership refers to a relationship or a feeling of ‘It is mine!’ between a consumer and a target of ownership, such as an object, an idea, or even another person. This sensation towards an object is ‘experienced as having a close connection with the self’ (Pierce et al., 2003). The essential part of this perception is that even though a customer does not legally own an item, place, or idea, they still have a strong bond with it (Nijs et al., 2021; Shaw et al., 2012; Verkuyten & Martinovic, 2017). Also, it has been observed that consumers will value and utilise things more effectively if they perceive ownership of the resource or object (Peck et al., 2020).

Digital firms believe that psychological ownership is linked to their future performance since it appears to be a desirable commodity to retain and capture virtual consumers (Jusiila et al., 2015; Morewedge et al., 2021). Researchers proposed that feeling that you own something virtually increases your level of admiration, intimacy and liking for that digital product or service (Kamleitner, 2015; Kirmani et al., 1999; Peck & Shu, 2009). Investment of time and effort in digital platforms and the products and services therein the customer results in the culmination of a bond with these digital products, which fosters sentiments of attachment. Despite the notion of who they are and which group they belong to, digital customers develop an attachment to the object of ownership (Dittmar, 1992; Kirk & Swain, 2018; Pierce et al., 2001). Customers therefore do not hesitate to refer to the desired virtual item as ‘theirs’.

Emotions

Nowadays, customers experience emotional attachment and a sense of ownership for goods they do not truly own but just think they do. In recent decades, there has been growing interest in the effects of emotion on customer behaviour and organisations (Elfenbein & Shirako, 2016). Emotions are a type of conscious mental reaction that manifests as intense feelings, usually toward a particular object and are frequently accompanied by physical, psychological and behavioural changes. Due to their relationship with the cognitive aspect (Dolcos et al., 2011; Vanneste et al., 2021), psychological aspect (Bartley, 2018), social aspect (Evans & Morgan, 2006; Hannula, 2012), and affective aspect (Skillmathing et al., 2020), customer emotions have drawn researchers’ attention. The customer’s interaction with technology is now a focus of this interest in emotions (Cho & Heron, 2015). Increasing our knowledge of emotions can help us comprehend how they interact with and are influenced by technological factors, which may enable us to make wiser judgments about the success of an organisation.

Emotions have a crucial role in psychological ownership, which consists of both affective and cognitive elements (Pierce et al., 2003). Customers’ feelings and emotions toward the target thing result in the target object becoming psychologically owned. Psychological ownership is influenced by emotions such as arousal, happiness, weirdness and pride (Kirk & Swain, 2018). In their experimental investigation, Shu and Peck (2011) discovered that emotions whether happy or sad had a substantial impact on customer’s positive affective reactions to the experimental object. They also proposed that emotions had a major role in customer’s feelings of psychological ownership (Pekrun et al., 2011).

Researches show the psychological arousal of consumers varies frequently, greatly, and is easily influenced, especially by the digital world. According to Watkins and Molesworth’s (2012) consumers who often interact with virtual worlds, slowly get attached to their virtual belongings. However, scholars further argued that these consumers experience the pleasure of bond with digital goods but occasionally they come across weirdness as a result of their intense attachment to something that is not physically present. In line with this, Kirk and Swain (2018) assumed that customers also had a strong feeling of loss and suffering when the digital assets they connect with, were lost due to technical difficulties. As a result, they also try to protect their virtual possessions through careful backups. So, interestingly, customers come across arousal and weirdness to be so attached to virtual goods, when customers recognised that they do not legally own these digital possessions (Kirk & Swain, 2018). The study of Kirk and Swain (2018) has, therefore, provided suggestions to the researchers for further exploration of the effect of several emotions towards psychological ownership. Additionally, it has been suggested that pride and happiness, as significant feelings, have a connection to psychological ownership. While hubristic pride amplifies the impact of psychological ownership on outcomes like economic valuation and word-of-mouth, genuine pride functions as an antecedent of psychological ownership (Kirk & Swain, 2015). However, the relationship between psychological ownership and various emotions in online user-generated content has not yet been fully explored (Kirk & Swain, 2018; Sinclair & Tinson, 2017).

Theoretical Framework

Psychological Ownership Theory

Pierce et al. (2003) attempted to explain the psychological state of ownership using the psychological ownership theory, which offers in-depth explanations of the phenomenon. As Pierce et al. (2003) asserted, ‘the meaning and emotion associated with my or mine and our’ are manifestations of the sense of ownership. The concept of psychological ownership depicts a connection between the customer and the product. The customer’s possessive feelings about items extend beyond the idea of legal possession and are in particular, psychological in origin. Customers’ possessions both tangible and intangible are emotional objects (Belk, 1989).

Researchers have identified psychological ownership’s motivations, including efficacy and effectivity, self-identity, having a home and stimulation (Jussila, 2015), which give the idea of psychological ownership in rationality. According to Beggan (1991), Dittmar (1992), Pierce et al. (2003), the customer starts to exert control over the product when they are successful in their endeavours to experience desire and the growth of ownership. Customers are thus encouraged to investigate their digital environment, associate, gather with it, interact with it, and think about its significance. The customer tends to see the target as their own and merge with their expanded self as they starts to control, deeply comprehend and become entirely engrossed in the thing (Dittmar, 1992; Pierce et al., 2003). According to Duncan and Hoffman (1981), when a customer feels a sense of ownership of a product and finds a safe environment to operate in, there is a fusion between the self and the thing. By engaging in these behaviours, a psychological ownership of the specific good or service is created.

Also Astryan and Oh (2008) and Jussila (2015) have demonstrated a number of psychological ownership antecedents, such as exercising control, getting to know something well, investing in oneself, and many more, which have shown the intended consequences for both customers and businesses. According to studies (Belk, 1988; Furby, 1978), a customer’s level of control over an item makes it feel more like a part of them and fosters feelings of ownership of that item. Kirk and Swain (2015) propose that technological control and interactivity foster the development of psychological ownership in the digital environment. Further, as customers become intimately familiar with certain products and link themselves with them, emotions of ownership develop in both the physical and digital worlds (Kirk & Swain, 2018; Pierce et al., 2001). Last but not least, according to Rochberg-Halton (1981), a person should establish sentiments of ownership for a particular thing by investing time, ideas and talents, as well as physical, psychological and intellectual energies into it. In line with this, Kirk and Swain (2018) found that digital customers make an effort, to engage with the virtual world, and invest in it in order to mentally own the product.

The dimensions of psychological ownership, such as self-efficacy, self-identity, belongingness, accountability, autonomy, responsibility and territoriality, have also been organised by researchers and serve as the cornerstone of the psychological ownership theory. Psychological ownership was initially based on the three qualities of self-efficacy, self-identity and belongingness by Pierce et al. (2001). However, after a thorough examination of the literature, the construct has since been expanded by the division and classification of the psychological ownership dimensions as either promotion-oriented or prevention-oriented (Avey et al., 2009; Olckers, 2013). Because of this, psychological ownership is a multi-dimensional construct that includes self-efficacy, self-identity, belongingness, accountability, autonomy and responsibility as positive or promotion-oriented dimensions and territoriality as a negative or prevention-oriented dimension that influences how much psychological ownership is felt.

The theory of psychological ownership, which is most relevant to digital technologies for the establishment of psychological ownership, contends that specific characteristics of the ownership object are necessary for consumers to be able to experience a sense of ownership (Pierce et al., 2003). More importantly, ownership focuses on the requirement to satiate psychological ownership motives in digital consumers. To meet the self-identity purpose, they must, in other words, be appealing and relevant to the self. They must also be open, available, affordable and accessible so that users can establish a sense of place or home within the confines of the digital world (Kirk & Swain, 2018). According to Baxter et al. (2015) and Norman (2013), conceivable interactions with digital commodities and their use based on the characteristics of the object and the user are necessary for psychological ownership to endure. The three paths to psychological ownership controlling an ownership target, getting to know a target well, or investing oneself in a target are also perceived as stimulating and facilitating having a place or feeling at home (Pierce et al., 2003; Pierce & Jussila, 2011). Therefore, a digital technology’s affordances are its features that enable users to complete specific activities and take specific actions. As a result, users’ abilities to feel a sense of ownership over a digital goal are both limited and increased by digital affordances (Kirk & Swain, 2018). On the contrary, some researchers also have suggested that keeping other things aside, consumers experience lower psychological ownership for digital products due to lower perceptions of control than physical products and thus have pointed towards the need for further exploration and research in the concerned area (Atasoy & Morewedge, 2018).

Entity Theory of Intelligence

According to Molden and Dweck’s (2005) Entity Theory of Intelligence, customers may come to believe that their intellect and abilities are inborn traits they possess and cannot be altered, increased, or lessened. Customers, who are acknowledged and rewarded for their characteristics rather than their accomplishments, grow to believe in themselves and experience emotions like pride, happiness, power, security and confidence. By demonstrating the importance of emotions in promoting psychological ownership, this theory serves as the foundation for the suggested theoretical framework. In contrast to young customers who are born with the traits of technological advancements and feel at ease with technology like online gaming, music, online shopping, digital transactions, education, etc., it is typically observed that elderly customers who are unfamiliar with the technological world have developed the feeling that the technological world is not their cup of tea. Therefore, it shows that the entity theory of intelligence has roots for the germination of emotions to lead towards psychological ownership via the dimension of self-efficacy, self-identity and more (Mullins & Sabherwal, 2020; Puche et al., 2016). Emotions can thus be employed to increase the customer’s psychological ownership of intangible goods and services in the digital sphere via the entity theory of intelligence. Thus, a particular motivational style that has a direct impact on a consumer’s feelings and emotions is supported by the idea that emerges from the entity theory of intelligence.

Incremental Theory of Intelligence

Additionally, the incremental theory of intelligence (Molden & Dweck, 2005) claims that intellect and other attributes are acquired via effort and experience. According to this notion, intellect is changeable and may be developed with effort and time. Therefore, through an incremental theory of intelligence, customers who are recognised for their effort develop cravings and emotions like ambition, pride, excitement, passion and anxiety, which can lead to the development of psychological ownership. For instance, the young generation of today is at ease with technology because they have a close relationship with it and put a lot of effort into learning about and staying in tune with technological advancements every day. These are the customers with growth mindsets (Lee et al., 2012). Similarly, digital consumers who believe in increasing their capacity through rigorous efforts have emotions like excitement, energetic feelings and happiness that again pop-up dimensions of psychological ownership, that is, self-identity, belongingness, accountability, etc. Therefore, this indicates that the incremental theory of intelligence has a foundation of developing emotions leading towards psychological ownership through its various dimensions like belongingness, accountability, etc. As a result, they have become psychologically accustomed to it and feel at ease with it. According to the current study, businesses can use the basis of this theory to plant the seeds of psychological ownership for the target objects in the brains of their clients.

Furthermore, studies have demonstrated that consumer support for incremental versus entity theories of intelligence reliably predicts whether or not a customer in a difficult situation would persevere (Molden & Dweck, 2005). The present study’s foundation is thus provided by these implicit theories of intelligence, which also have consequences for how emotions and beliefs are handled and processed. It makes feel worthless for businesses to invest time and effort in such customers if they think intelligence or ability is fixed. However, if one’s intelligence or skill is thought to be a sign of diligent effort, it indicates the need to continue making attempts and go forward. As a result, customers may exhibit a more optimistic attitude and perform better (Blackwell et al., 2007), which is advantageous for businesses.

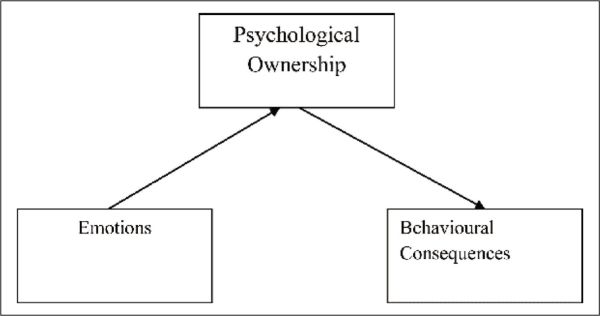

Hence, these theories pose the fundamental base to achieve the objectives of the current study, that is, to propose a theoretical framework that explains the existence of psychological ownership in digital technologies and to theoretically examine the role of emotions in enhancing the psychological ownership for digital products and services (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Conceptual Model.

Source: Conceptual model through literature review.

Discussion and Implications

It is necessary to look at how digital technologies are affecting customers because they have altered the interaction between consumers and their goods. Technology advancements have replaced the models in which people are legal owners of private material goods with access-based consumption models. Here under the new consumption model, customers temporarily purchase the right to utilise shared, experienced products (Bardhi & Eckhardt, 2012; Eckhardt et al., 2019; Morewedge et al., 2021; Rifkin, 2001). Therefore, this research study aimed to comprehend how customer behaviour is impacted by the expansion of digital technology, which in turn influences digital firms. The theoretical framework is applicable more generally to areas with significant use of digital technology, and it is instructive and suggestive for managers working to draw and keep customers in these brand-new digital environments.

Further, due to the widespread adoption of digital technology, consumer consumption and behavioural patterns have also changed significantly, creating both a threat and an opportunity for the online sector. Since psychological ownership is a valuable asset for digital firms since it has value-enhancing results, modern digital enterprises must transform risks and cultivate new chances for creating psychological ownership among customers (Morewedge et al., 2021).

Also, how consumer emotions are connected in the virtual world needs thorough investigation in the context of psychological ownership. The relationship between psychological ownership and emotions had not been fully explained in the marketing literature, (Watkins, 2016), and it seemed vague in the context of digital virtual goods, such as e-books, music, games and digital content. Customers tend to be more positively affected by things towards which they feel an emotional connection, such as happiness, arousal, pride, etc., (Schultz & Schultz, 1989). Because people value their relationship with the object and wish to preserve it, experiencing this emotional bond with the target online objects can also lead to certain psychological behaviours. Therefore, it becomes crucial in the current online era to research the impact of various emotions on perceived ownership of virtual commodities which was made fruitful via this study.

The study also theoretically shows how emotions can strengthen a customer’s sense of psychological ownership over the online space, which would have a good knock-on effect on digital businesses. In order to better understand how emotions affect psychological ownership and how their worth may be increased for businesses, the study would be helpful to marketers and digital firms. In order to get the intended results for the businesses, it would assist them in developing efficient ways to acquire, manage and cultivate psychological ownership of the customers.

Emotions of consumers shown in advertising, build a connection between the customer and the firm. This emotional connection results in long-term customer commitment and loyalty to the businesses. Emotions also work well in the digital realm to foster deeper connections between users and virtual technology, creating a sense of psychological ownership over the desired goods. Therefore, this study provides managers with how to create positioned methods for marketing products that might generate profit from utilising customers’ emotions to create psychologically favoured goods and services.

The study significantly adds to the body of marketing literature. In order to explain the relationship between psychological ownership and emotions in the context of digital technologies, the study has presented a theoretical framework based on psychological ownership theory, entity theory of intelligence and incremental theory of intelligence. This framework could aid firms in formulating better strategies for their future success paths.

This study will be important for digital firms and marketers since it will help in the development of customer satisfaction and retention tactics that leverage psychological ownership. Additionally, in the modern internet era, psychological ownership and emotions are equally important for understanding client behaviour. As a result, the study provided necessary insights into how emotions can improve psychological ownership in the setting of digital technology.

Future Research and Conclusion

Despite the significant effort put forth, there are still loopholes and gaps in this study that need to be filled by scholars and researchers as future research opportunities. The theoretical framework only provides conceptual support to the existence of psychological ownership in digital technologies and it also shows the impact of emotions in enhancing psychological ownership. Further, customers’ feelings and psychology may differ across countries or depending on their demographic profile as well. Therefore, empirical research in this area is advised, with a potential focus on demographic or cultural differences. To better understand psychological ownership as a comprehensive concept, additional constructs may be examined with emotions.

Thus, it is clear that the emergence of new digital technologies has ushered in a new era of digital consumption, which is putting tremendous pressure on the industry’s enterprises. However, it is also widely accepted and recognised that psychological ownership is a significant asset for the company because it can result in a number of outcomes that increase value. As a result, the current study will aid digital businesses in this regard by assisting them in understanding emotions and significant aspects of psychological ownership that will help the organisations in reaching favourable outcomes.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Shelleka Gupta  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9813-3252

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9813-3252

Asatryan, V. S. (2006). Psychological ownership theory: An application for the restaurant industry. Iowa State University.

Asatryan, V. S., & Oh, H. (2008). Psychological ownership theory: An exploratory application in the restaurant industry. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 32(3), 363–386.

Atasoy, O., & Morewedge, C. K. (2018). Digital goods are valued less than physical goods. Journal of Consumer Research, 44(6), 43–57.

Avey, J. B., Avolio, B. J., Crossley, C. D., & Luthans, F. (2009). Psychological ownership: Theoretical extensions, measurement and relation to work outcomes. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior, 30(2), 173–191.

Bardhi, F., & Eckhardt, G. M. (2012). Access-based consumption: The case of car sharing. Journal of Consumer Research, 39(4), 881–898.

Bartley, S. R., & Ingram, N. (2018). Parental modelling of mathematical affect: Self-efficacy and emotional arousal. Mathematics Education Research Journal, 30, 277–297.

Baumeister, C., & Wangenheim, F. V. (2014). Access vs. ownership: Understanding consumers’ consumption mode preference. Ownership: Understanding Consumers’ Consumption Mode Preference (July 7, 2014).

Baxter, W. L., Aurisicchio, M., & Childs, P. R. (2015). A psychological ownership approach to designing object attachment. Journal of Engineering Design, 26(4–6), 140–156.

Beggan, J. K. (1991). Using what you own to get what you need: The role of possessions in satisfying control motivation. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 6(6), 129.

Belk, R. W. (1988). Possessions and the extended self. Journal of Consumer Research, 15, 139–68.

Belk, R. W. (1989). Extended self and extending paradigmatic perspective. Journal of Consumer Research, 16(1), 129–132.

Blackwell, L. S., Trzesniewski, K. H., & Dweck, C. S. (2007). Implicit theories of intelligence predict achievement across an adolescent transition: A longitudinal study and an intervention. Child Development, 78(1), 246–263.

Cho, M. -H., & Heron, M. L. (2015). Self-regulated learning: The role of motivation, emotion, and use of learning strategies in students’ learning experiences in a self-paced online mathematics course. Distance Education, 36, 80–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022242920957007

Dittmar, H. (1992). Perceived material wealth and first impressions. British Journal of Social Psychology, 31(4), 379–391.

Dolcos, F., Iordan, A. D., & Dolcos, S. (2011). Neural correlates of emotion–cognition interactions: A review of evidence from brain imaging investigations. Journal of Cognitive. Psychology, 23, 669–694.

Duncan, G. J., & Hoffman, S. D. (1981). The incidence and wage effects of overeducation. Economics of Education Review, 1(1), 75–86.

Eckhardt, G. M., Houston, M. B., Jiang, B., Lamberton, C., Rindfleisch, A., & Zervas, G. (2019). Marketing in the sharing economy. Journal of Marketing, 83(5), 5–27.

Elfenbein, H. A. (2016). Individual differences in negotiation: A nearly abandoned pursuit revived. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 24(2), 131–136.

Evans, J., Morgan, C., & Tsatsaroni, A. (2006). Discursive positioning and emotion in school mathematics practices. Educational Studies Mathematics, 63, 209–226.

Furby, L. (1978). Possession in humans: An exploratory study of its meaning and motivation. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 6(1), 49–65.

Hannula, M. S. (2012). Exploring new dimensions of mathematics-related affect: Embodied and social theories. Research in Mathematics Education, 14, 137–161.

Jussila, I., Tarkiainen, A., Sarstedt, M., & Hair, J. F. (2015). Individual psychological ownership: Concepts, evidence, and implications for research in marketing. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 23(2), 121–139.

Kamleitner, B. (2015). When imagery influences spending decisions. Zeitschrift fur Psychologie. https://doi.org/10.1027/2151-2604/a000077

Kamleitner, B., & Erki, B. (2013). Payment method and perceptions of ownership. Marketing Letters, 24(1), 57–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-012-9203-4

Kathan, W., Matzler, K., & Veider, V. (2016). The sharing economy: Your business model’s friend or foe? Business Horizons, 59(6), 663–672.

Kim, S., Kim, S. -G., Jeon, Y., Jun, S., & Kim, J. (2015). Appropriate or remix? The effects of social recognition and psychological ownership on intention to share in online communities. Human–Computer Interaction, 31(2), 97–132.

Kirk, C. P., Peck, J., & Swain, S. D. (2018). Property lines in the mind: Consumers’ psychological ownership and their territorial responses. Journal of Consumer Research, 45(1), 148–168.

Kirk, C. P., & Swain, S. D. (2015). Interactivity and psychological ownership in consumer value co-creation. In Ideas in marketing: Finding the new and polishing the old (pp. 121–121). Springer.

Kirk, C. P., & Swain, S. D. (2018). Consumer psychological ownership of digital technology. In J. Peck & S. B. Shu (Eds.), Psychological ownership and consumer behavior (pp. 69–90). Springer.

Kirmani, A., Sood, S., & Bridges, S. (1999). The ownership effect in consumer responses to brand line stretches. Journal of Marketing, 63(1), 88–101.

Lee, H. K., Choi, H. S., & Ha, J. C. (2012). The influence of smartphone addiction on mental health, campus life and personal relations—focusing on K university students. Journal of the Korean Data and Information Science Society, 23(5), 1005–1015.

Lessard, B. S., & Chebat, J. -C. (2015). Psychological ownership, touch and willingness to pay for an extended warranty. Journal of Marketing Theory & Practice, 23(2), 224–234.

Li, D. & Atkinson, L. (2020). The role of psychological ownership in consumer happiness. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 37(6), 629–638.

Molden, D. C., & Dweck, C. S. (2005). Finding “meaning” in psychology: A lay theories approach to self-regulation, social perception, and social development. American Psychologist, 61(3), 192.

Morewedge, C. K., Monga, A., Palmatier, R. W., Shu, S. B., & Small, D. A. (2021). Evolution of consumption: A psychological ownership framework. Journal of Marketing, 85(1), 196–218.

Mullins, J. K., & Sabherwal, R. (2020). Gamification: A cognitive-emotional view. Journal of Business Research, 106, 304–314.

Nijs, T., Martinovic, B., Verkuyten, M., & Sedikides, C. (2021). ‘This country is OURS’: The exclusionary potential of collective psychological ownership. British Journal of Social Psychology, 60(1), 171–195.

Norman, D. (2013). The design of everyday things: Revised and expanded edition. Basic Books.

Olckers, C. (2013). Psychological ownership: Development of an instrument. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 39(2), 1–13.

Peck, J., Barger, V. A., & Webb, A. (2013). In search of a surrogate for touch: The effect of haptic imagery on perceived ownership. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 23(2), 189–196.

Peck, J., Kirk, C. P., Luangrath, A. W., & Shu, S. B. (2020). Caring for the commons: Using psychological ownership to enhance stewardship behaviour for public goods. Journal of Marketing, 85(2), 1–17.

Peck, J., & Luangrath, A. W. (2023). A review and future avenues for psychological ownership in consumer research. Consumer Psychology Review, 6(1), 52–74.

Peck, J., & Shu, S. B. (2009). The effect of mere touch on perceived ownership. Journal of Consumer Research, 36(3), 434–447.

Peck, J., & Shu, S. B. (2018). Psychological ownership and consumer behavior. Springer Publishing

Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., Frenzel, A. C., Barchfeld, P., & Perry, R. P. (2011). Measuring emotions in students’ learning and performance: The achievement emotions questionnaire (AEQ). Contemporary Educational Psychology, 36(1), 36–48.

Pierce, J. L., & Jussila, I. (2011). Psychological ownership and the organizational context: Theory, research evidence and application. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Pierce, J. L., Kostova, T., & Dirks, K. T. (2001). Toward a theory of psychological ownership in organizations. The Academy of Management Review, 26, 298–310. https://doi.org/10.2307/259124

Pierce, J. L., Kostova, T., & Dirks, K. T. (2003). The state of psychological ownership: Integrating and extending a century of research. Review of General Psychology, 7(1), 84–107.

Puche, J., Ponte, B., Costas, J., Pino, R., & De la Fuente, D. (2016). Systemic approach to supply chain management through the viable system model and the theory of constraints. Production Planning & Control, 27(5), 421–430.

Rifkin, J. (2001). The age of access: The new culture of hypercapitalism. Penguin.

Rochberg-Halton, E., & Halton, E. (1981). The meaning of things: Domestic symbols and the self. Cambridge University Press.

Schultz, D. E., & Schultz, H. F. (1989). Transitioning marketing communication into the twenty-first century. Journal of Marketing Communications, 4(1), 9–26.

Shaw, A., Li, V., & Olson, K. R. (2012). Children apply principles of physical ownership to ideas. Cognitive Science, 36(8), 1383–1403.

Shu, S. B., & Peck, J. (2011). Psychological ownership and affective reaction: Emotional attachment process variables and the endowment effect. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 21(4), 439–452.

Sinclair, G., & Tinson, J. (2017). Psychological ownership and music streaming consumption. Journal of Business Research, 71, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres. 2016.10.002

Skillmathing, K., Bobis, J., & Martin, A. J. (2020). The ‘ins and outs’ of student engagement in mathematics: Shifts in engagement factors among high and low achievers. Mathematics Education Research Journal, 33(3) 469–493.

Vandewalle, D., Van Dyne, L., & Kostova, K. (2003). Psychological ownership: An empirical examination of its consequences. Group & Organization Management, 20(2), 210–226.

Vanneste, P., Oramas, J., Verelst, T., Tuytelaars, T., Raes, A., Depaepe, F., & Van den Noortgate, W. (2021). Emotion and cognition detection: A use case on student engagement. Computer Vision and Human Behaviour, Mathematics, 9, 287.

Verkuyten, M., & Martinovic, B. (2017). Collective psychological ownership and intergroup relations. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12, 1021–1039. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691617706514.

Watkins Jr, C. E. (2016). Listening, learning, and development in psychoanalytic supervision: A self psychology perspective. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 33(3), 437–471. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038168

Watkins, R., & Molesworth, M. (2012). Attachment to digital virtual possessions in videogames. Research in Consumer Behavior, 14, 153–171.